New Romantic Cinema Has Arrived in America

How Superman, Sinners, and auteurist cinema are breaking the chains of systematic thinking

In 2025, American cinema is having a New Romantic moment.

The box office and film discourse have been dominated by films addressing the central question of our age: How do we live amidst growing dissolution and disappointment in our institutions and ideologies?

The defining principles of New Romantic cinema: Human stakes over systems and political ideologies. Auteurist vision over house style. Emotional truth over conformist entertainment. Experiences that resist easy quantification.

Ryan Coogler’s Sinners became the best opening for an original film this decade. James Gunn’s Superman beat Marvel’s latest offering in box office, critical acclaim and overall buzz.

Zach Cregger’s Weapons found success through horror, humor and Magnolia references. Celine Song’s Materialists revived the New York romance with a controversial exploration of 21st century dating.

My favorite films of the year and probably the decade—Ari Aster’s Eddington and Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another—offer fearless, dynamic and explosive (literally) takes on the current American landscape. These films explore polarization without embracing exhausted ideologies, choosing to see people instead of political straw men.

“The defining principles of New Romantic cinema: Human stakes over systems. Auteurist vision over house style. Emotional truth over systematized entertainment.”

Having just had the opportunity to immerse myself in this movement at the New York Film Festival, it’s clear that it’s growing exponentially. New adherents could be found among the enthusiastic sold out audiences for the secret screening of Marty Supreme but also No Other Choice, Nouvelle Vague, Blue Moon, Is This Thing On, Jay Kelly, Sentimental Value and others that dominated the discourse among festival-goers.1

The Romantic Parallel

The Romantic movement was the bloody cry against industrial rationalism. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein warned that science without wisdom creates monsters. William Blake declared imagination more vital than reason. Beethoven shattered Classical form to reach emotional truth.

In 1802, Beethoven was 31 years old and contemplating suicide. His deafness was accelerating. He retreated to Heiligenstadt, isolated and despairing. But in 1803-1804, he emerged transformed, composing the Eroica Symphony—a work so radical it invented an entirely new emotional vocabulary.

The Eroica refused Classical balance for dramatic intensity. Where Mozart wrote symphonies that moved with clockwork precision, the Eroica surged and retreated unpredictably, building to emotional climaxes that shattered formal conventions. Beethoven broke Classical form because emotional truth demanded it. He wrote music that thinks through feeling, that makes philosophical concepts physically felt.

In 2023, music critic Ted Gioia predicted: “We need a new Romanticism, and we’ll probably get one.” Later that year, Ross Barkan documented the signs—young people ditching smartphones, physical literary scenes returning.

And now the New Romantic movement has dominated mainstream cinema in 2025.

After decades of bland, formulaic, CGI-slopified franchise “content,” and in advance of an impending “AI revolution,” this New Romantic vanguard offers cinema that thinks through feeling, that makes philosophical concepts physically felt, that insists human connection resists quantification and transcends polarization.

A New Romantic Thesis: Kindness is Punk Rock

The Romantics criticized rationalist systems—whether revolutionary or reactionary— as they tend to subordinate human relationships to abstract principles. William Blake called them “mind-forg’d manacles.” These chains built from systematic thinking imprison us more completely than any physical restraints.

So it’s fitting that Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s Superman breaks his chains as the opening to the new era DC films. James Gunn’s Superman stands as thesis statement for the entire New Romantic movement.

Superman demands its audience question whether they could choose hope—not optimism, not naivete, but deliberate hope in people, goodness, and love as radical act against systematic thinking. From the first time Siegel and Shuster put pen to paper, Superman has stood beyond political ideology and for essential human values. Kindness. Truth. Justice. Goodness.

Not deconstructed goodness. Not “complicated” goodness that’s actually moral compromise. Just goodness—four-color, sincere, unabashed, unapologetic. Gunn’s brilliance is understanding that in 2025, just as in 1938, these are radical stances. Despite his alien origins, Gunn restores Superman’s status as the most humanist superhero. He knows the names of the civilians Luthor mindlessly kills. He rejects his “true” Kryptonian mission in favor of humanity. He saves the squirrel.

Superman means a lot to me personally. This film understands why Superman should mean something to everyone.

Compare this to Marvel’s decade-long approach where every hero must be “complicated”—morally compromised, emotionally hedged, sincerity undercut with jokes to protect audiences from feeling too much.

Superman refuses that protection completely. In an age trained to distrust genuine feeling, Gunn offers radical earnestness as revolutionary act, reclaiming hope and sincerity against rationalist cynicism.

The Great American Crack Up

Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another and Ari Aster’s Eddington both open with the same question: What is wrong with America?

One Battle After Another asks it directly. Are we racist militarist right-wing psychopaths? Marxist terrorists hung up on pedantic language? The film’s response: Politics are pretext. Violence belongs to everyone equally. The ideological labels are costumes we wear to justify what we were already going to do.

The only heroes stay true to their families. Everyone else is playing a fake war. The Christmas Adventurers need their cause. The French ‘75 need their revolution. They ruin real human lives to sustain fantasies of political meaning.

Eddington asks it differently: Was it the culmination of long-standing injustices finally laid bare? Or were we all just stuck inside, afraid and powerless, and we went a little funny in the head?

The answer is probably both. But Eddington understands the question itself misses the point. What matters isn’t what cracked but how it cracked—and what’s growing through the rupture.

Fear and frustration twist the mind. They give license to our worst impulses. Eddington takes us back to May 2020 and shows the very human path toward anger and violence. A film without heroes that refuses to take sides politically because it understands the crack wasn’t political—it was psychological. We all went a little mad.

Both films reach the similar conclusions: systematic thinking—whether left-wing or right-wing, political or technological—failed America completely. The ideologies we used to make sense of the world became the very things destroying human connection.

Where One Battle After Another shows families surviving fake political wars by staying true to each other, Eddington strips away every systematic answer to reveal the terrifying truth: the algorithms and systems have us perform a terrible dehumanizing act, while forces that prey upon us advance.

The great American crack-up created an opening where systematic thinking failed. These films show growing through that rupture is the insistence that the only thing worth preserving is human connection—messy, unpredictable, unquantifiable.

Love Against Systemization

Celine Song’s Materialists asks: Can love survive when we try to optimize it?

The film’s title operates as provocation: yes, we’re material beings in material cities with material constraints. And despite all that, love thrives in those material conditions if we choose honesty and imperfect fulfillment.

Song knows and loves New York—the real city with its specific neighborhoods and class stratifications. Her materialism operates on two levels: literal (the physical city, economic realities making love difficult) and philosophical (can authentic human connection exist when capitalism treats everything as commodity?).

Her main character, played by Dakota Johnson with deft iciness, initially embodies this commodification. She’s a matchmaker with lists of systemic reasons for successful relationships: height, wealth, education, economic background. Data points that promise to deliver perfect matches through optimization.

Materialists embraces a full-throated understanding of perfection’s appeal, but Song insists that real love operates by an entirely different logic.

Yet the dream of systematic matchmaking is so fierce that many critics thoughtlessly called the film “broke-boy propaganda.” Materialists struck that nerve because so many have committed to the idea that relationships can be optimized, that the right formula delivers the perfect list of qualities rather than an imperfect but lovable human being.2

Her lovers choose each other not because it makes economic sense but because human connection transcends economic calculation. Romantic era writers like Jane Austen wrote novel after novel proclaiming that the world resists our attempts at systemization in matters of love.

Song picks up this torch by allowing for love without fantastical pretenses that material conditions either don’t exist or don’t matter.

The New Romantic stance embraces the reality that human connection operates by its own logic, resists quantification, and survives even when systems promise easier paths.

The Gothic Turn

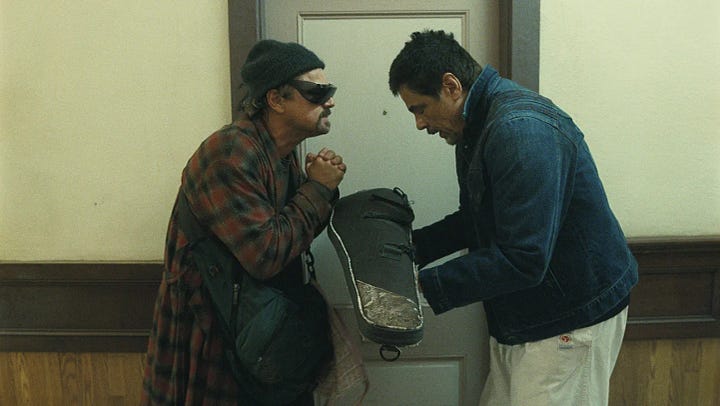

There’s a scene late in Ryan Coogler’s Sinners where the devil sits down for a drink with our protagonist. Not to terrorize him. Just to reminisce. Kick around old times with an old friend. Hear those real Blues.

It’s one of the most unsettling moments I’ve experienced in a theater this year. It’s intimate and seductive, not traditionally horrifying. Yet the devils that plague us aren’t some impersonal force like Thanos, but someone you know. Someone who’ll gladly buy the next round and truly, truly appreciates the good shit.

I didn’t know Coogler had a movie like this in him. It is one of the more powerful films about the true nature of the devil I’ve seen. And while I Ioved Robert Eggers’s Nosferatu and its classic Gothic vision of the devil as all-encompassing darkness, sickness and contagion — Sinners knows better.

Sinners knows the true lies the devil shares. That we have more in common with the devil than we like to admit. That sometimes, it’s good to have a drink with him and think through old times.

The early Romantics understood something contemporary horror had forgotten in favor of shock and gore: Evil isn’t an external force that stalks us without reason. It’s intimate. Personal. Human-scale. An inclination we all share if left unchecked.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) isn’t about a monster invading from outside. It’s about Victor creating something through his own choices, abandoning it, then being destroyed by what he made. The creature becomes monstrous through Victor’s failure of human connection.3

Sinners goes back to this earliest Gothic tradition. Not invasion but invitation. The devil isn’t Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), some foreign contagion invading England. The devil in Sinners is your brother whom you invited in. Who knows your weaknesses because you shared them.

The film draws from From Dusk Till Dawn and every folk tale about Charlie Patton and Robert Johnson at the crossroads—but it understands these aren’t about supernatural deals.

They’re about the human capacity to choose what destroys us.

Zach Cregger’s Weapons takes Shelley’s logic and inverts it. If Frankenstein is about creating life that destroys us, Weapons is about preventing death until it becomes monstrous.

The film’s Gothic genius is making its central question visual: What if our desperate refusal to accept natural cycles—death, loss, the world moving on without us—became physical? What if the sacrifice of the best years of our lives and of our children were made tangible? What if you could see our inability to let go?

The best horror movies capture persistent existential dread. Not spectacle. That low-grade terror that something fundamental has gone wrong with the world, and no system can fix it. Weapons lets that dread seep into you—like waking up on a bad day, in a bad month, in the current era. And then it shows you why.

Cregger constructs his horror through accumulation rather than shock. Every scene adds another layer of wrongness, that persistent sense that something fundamental has broken. The film doesn’t offer jump scares. It offers the more terrifying recognition: we’ve been trying to optimize our way out of mortality, and that refusal to accept limits has consequences.

The demon in Weapons isn’t evil—it’s sympathetic, even tragic. Human enough to inspire kindness, empathy and pity. It’s what happens when love curdles into control, when care becomes refusal to release, when we try to systematize life itself until we’ve created something that should have been allowed to die.

Both films generate genuine sympathy for their demons. Because the demons are us. In Sinners, we’re making deals we know we’ll regret. In Weapons, we’re clinging to control, trying to engineer our way out of mortality.

Where New Romantic cinema’s humanist films find grace in everyday relationships, its Gothic wing finds terror in our refusal of those relationships. Its villains choose deals over connection, control over acceptance, fighting death rather than ceding the world to renewal.

“The devils that plague us aren’t some impersonal force like Thanos, but someone you know. Someone who’ll gladly buy the next round.”

The Seeds of New Romanticism

The signs were there for years. A24 was the vanguard—quietly building a roster of films that rejected systematic thinking in favor of auteurist vision and emotional complexity.

Alex Garland’s Ex Machina (2015) warned about the seduction of artificial intelligence masquerading as human connection—a prescient critique of what tech culture promised versus what it delivered.

Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things (2023) used Frankenstein’s logic to explore bodily autonomy and the construction of self beyond societal systems. Delightfully demented and visually stunning, it celebrated a timeless struggle against degradation. Showing how human consciousness resists programming even when literally created in a lab. Willem Dafoe’s sympathetic Doctor proved that creation through care, not control, matters.

Jesse Eisenberg’s A Real Pain (2024) showed grief as irreducible human experience that resists therapeutic optimization. Everyone’s pain is particular but also common—the film insisted that wellness culture can’t systematize away what makes us human.

Even Greta Gerwig’s Barbie (2023)—massive Warner Brothers hit that it was—operated as Trojan horse. Wrapped in pink IP familiarity, Barbie was a film that rejects pre-programmed existence for messy, uncertain humanity. The Kens’ pursuit of patriarchal systems and Barbie’s choice of authentic imperfection over plastic perfection? Pure New Romantic cinema generating over a billion dollars at the multiplex.

Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist (2024) is the movement’s architectural manifesto. The film celebrates how true artistry forces your attention on what’s important and true. Its main character has long soliloquies standing against vulgar aesthetics and systemic cruelty. Corbet was rightly celebrated for a masterpiece about the timeless struggle to create meaning that can’t be commodified or controlled.

Sean Baker’s Anora (2024) captured New Romantic cinema at its most vital—brilliant, dreamlike, exciting, sexy and funny as hell. The film insists on seeing its characters as full humans whose love and ambition resist the easy categorizations that systematic thinking demands.

Now, in 2025, the major studios are finally responding. Warner Brothers has become the unlikely standard-bearer for New Romantic cinema at scale, betting on auteurist vision over franchise formulas. They gave Ryan Coogler unprecedented creative freedom on Sinners. They backed Superman with full creative control for James Gunn. And audiences responded—A Minecraft Movie crossed $950 million, Sinners opened to record numbers for an original film, Superman became a cultural phenomenon.

As David Ellison’s Paramount Skydance—fresh off acquiring Paramount with a franchise-focused approach—prepares a bid for Warner Brothers Discovery, the stakes couldn’t be clearer. Warner Brothers just rejected Paramount’s initial offer as too low, with CEO David Zaslav believing the company’s streaming and studio success warrants a “hefty premium.”

The box office triumph of New Romantic cinema isn’t just an aesthetic victory—it’s become Warner Brothers’ negotiating leverage, proof that auteurist vision delivers both critical acclaim and financial results worth protecting.

The New Romantic moment isn’t just about individual studios—it’s about an industry-wide recognition that audiences want something systematic thinking can’t deliver. They want to feel. They want surprise. They want human connection that resists quantification.

Film at Lincoln Center just had their best year of box office ever. Repertory screenings of classic films on 35mm and 70mm projections are becoming badges of honor. Letterboxd subscriptions are surging.

Audiences in the know are returning.

Eroica Anew

In 2023, Ted Gioia ended his essay predicting the New Romanticism with a question: “But what does that kind of music sound like? In 1800, it was Beethoven. And today?”

In 1804, Beethoven emerged from despair in Heiligenstadt and composed the Eroica—a symphony that refused to comfort audiences with Classical balance. It demanded they feel something genuine, something that couldn’t be systematized or predicted. It made philosophical concepts physically felt.

In 2025 cinema, an Eroica moment is happening anew. Auteurist films that explore political abstractions versus love and systemic obligations versus human connection, are resonating broadly.

Not because every film succeeds—some stumble, some fail—but because auteurs are refusing the systematic thinking that promised to perfect entertainment. These films trust audiences with complexity. They insist human connection matters more than any system claiming to optimize it away.

The system can’t account for the moment in Superman when he saves the squirrel. It can’t systematize the devil buying you a drink in Sinners. It can’t optimize why Materialists makes you want to call someone you shouldn’t. It can’t engineer the terror in Weapons or the family loyalty in One Battle After Another.

These moments prove that what matters most—love, goodness, grace, human connection—can’t be engineered, only experienced. Is it any wonder the cinema feels alive again?

Many companies have stated plainly they prefer we permanently plug into virtual worlds, consuming systematically optimized content or AI-generated slop. They want Marvel’s Classical precision—clockwork entertainment delivering expected pleasures without risk, franchise logic that turns art into asset management.

New Romantic cinema says no.

It says the most important things about being human can’t be reduced to data points or demographic targeting. It says being in the room together, experiencing art that resists every attempt to turn it into content, proves through collective feeling that human connection is the thing no system can replace.

Not data. Truth.

Not systems. Love.

Not content. Art.

We’re compiling a comprehensive list of New Romantic Cinema on Letterboxd—films from the past ten years that anticipated and now embody this movement. From Ex Machina to Eddington, from Barbie to One Battle After Another, these are the films reclaiming cinema’s capacity to make us feel without systematic mediation.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on the New Romantic movement, and films—American or global—that meet the definition.

Doug Hesney is the founder of the Cognitive Film Society and editor of Cognitive Frames. He’ll be sharing a full recap of our experiences at the New York Film Festival in our next “In the Room” newsletter.

We’ll have a full recap of our experiences at the New York Film Festival for our “In the Room” newsletter

The wonderfully funny newsletter Cartoons Hate Her brilliantly debunks these myths on a weekly, sometimes daily basis

And of course in the next 12 months we get both Guillermo Del Toro’s Frankenstein and Maggie Gyllenhaal’s The Bride.