The War of the Romantics

Recreating the First Culture War for Cinema. A response to FilmStack Challenge #7

Charlotte Simmons asked us to write about how we’d adapt a piece of media as film if we were given studio keys and a blank check.

I’d love to make a great War film. But not the kind you’re thinking.

Five months ago, I walked into the Metropolitan Opera for Fidelio—my second opera ever, first in the Beethoven-to-Wagner lineage. I own the Klemperer recording on vinyl. I’d studied Swafford’s Beethoven biography. I thought I understood what I was about to experience.

I understood nothing.

Sitting in Family Circle Row I, watching Lise Davidsen sing Beethoven’s revolutionary cry for freedom, I realized opera isn’t arias—it’s architecture. Every element—music, staging, performance, light—building toward something that can’t exist in any other form. This was Beethoven’s Eroica made flesh. Total art.

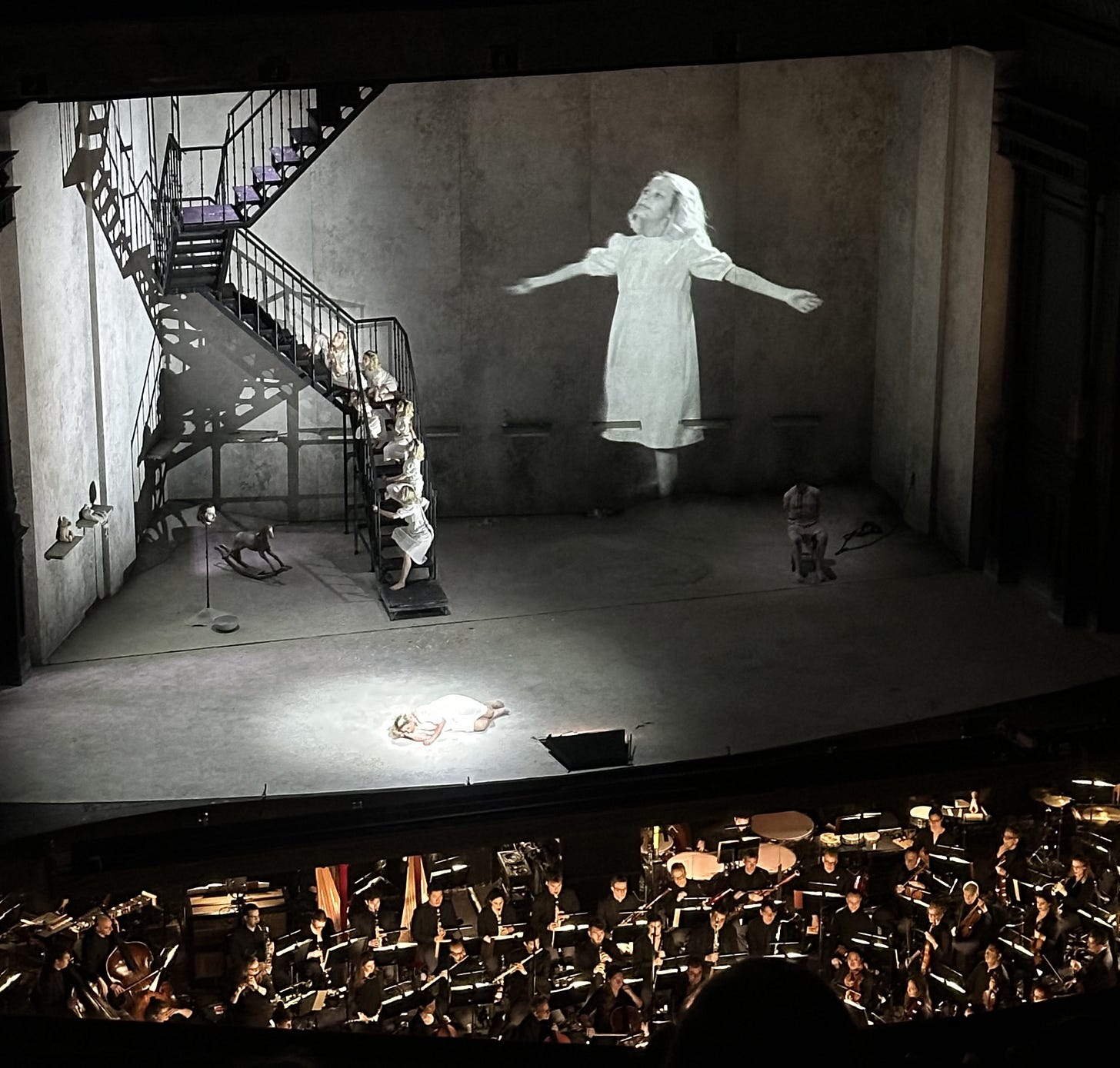

Two months later, Salome.

The most intense live theater experience of my entire life.

Strauss taking Wagner’s techniques and weaponizing them into psychosexual metal opera with severed heads and 50-foot ghosts.

And I kept thinking: How did we get from Beethoven’s revolutionary restraint to Strauss’s overwhelming excess?

What happened between 1805 and 1905 that made Salome possible—and made it so dangerous?

The answer is the War of the Romantics. The Brahms-Wagner rivalry. The original culture war where aesthetic choices became ideological battles that helped shape the 20th century’s catastrophes.

This is the film I want to make.

The Deepest Well of Music

Despite a long interest in rock, country, blues and Jazz, the world of “Classical Music” had always seemed fairly impenetrable. But once you dig into it, and meet the music for the times and intent it was written, it becomes far more accessible. These were after all popular artists.

Their music made them famous and rich (in Brahms’s case anyway). Their music was not meant to be admired on a pedestal - but lived in and experienced deeply.

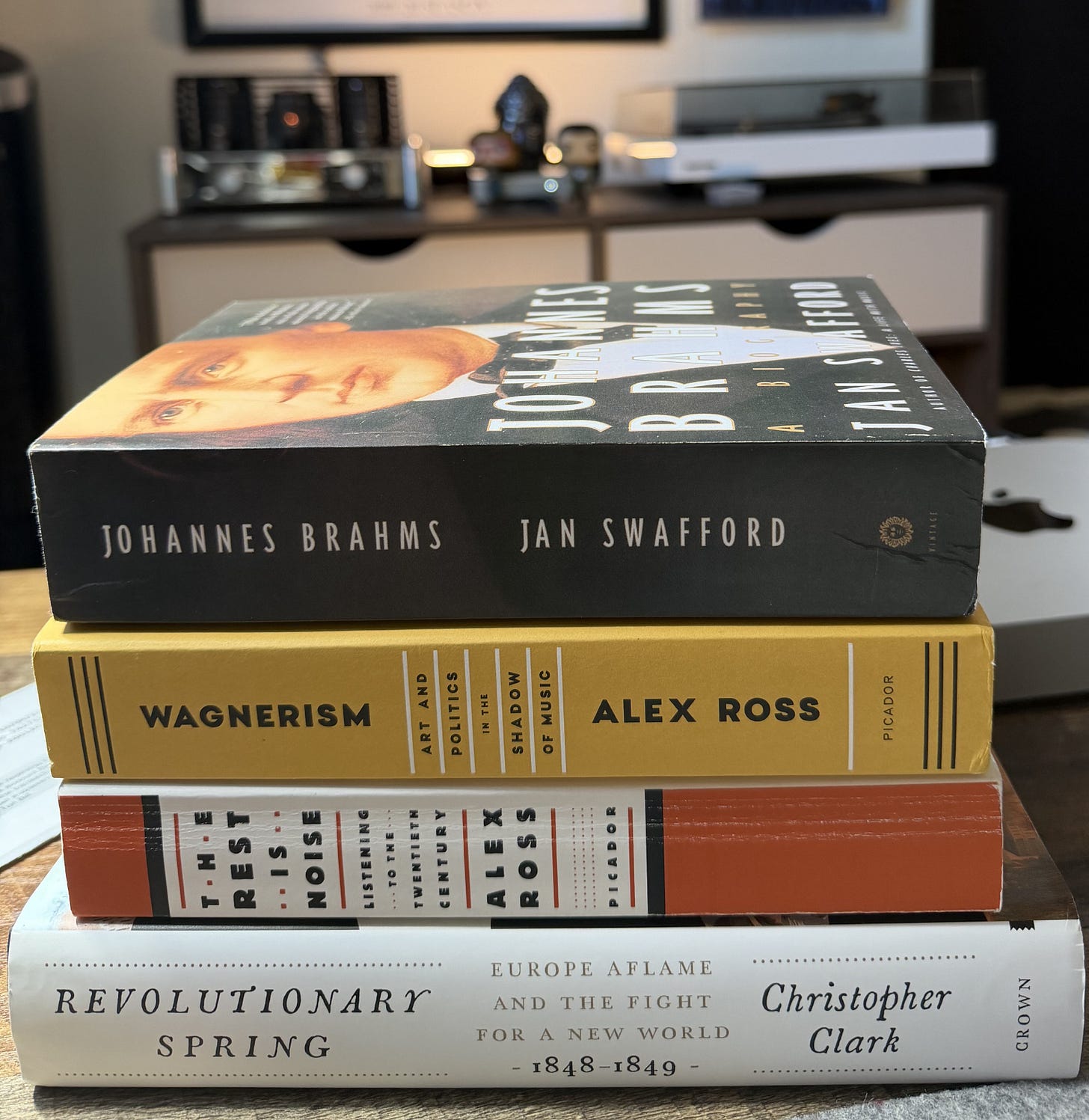

Since that initial Beethoven biography, I’ve been reading and listening my way further and further into this world. These are some of the best books I’ve read on the era (so far) and what I’d base my adaptation upon:

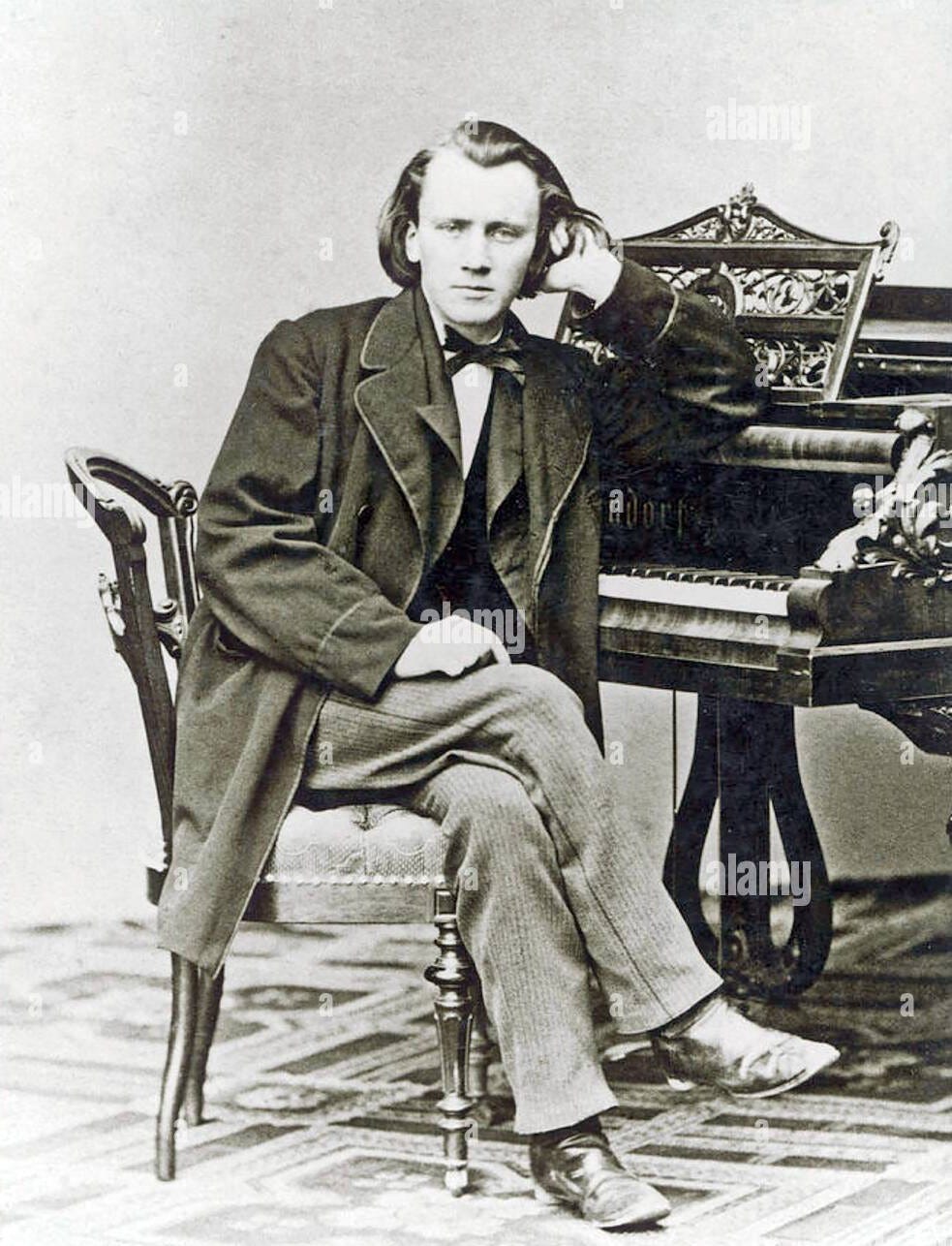

Jan Swafford’s Brahms: A Biography has prominent place in my music library. It’s where I learned that Brahms’s conservatism was revolutionary restraint. The discipline required to write absolute music in an age demanding theatrical spectacle was its own radicalism. Swafford provides Caro level detail into both the music composition and the life of his subjects. Both his Beethoven and Brahms biographies are must reads for any burgeoning classical music fan.

Alex Ross’s The Rest is Noise opens with a scene-setting tour de force: May 1906 in Graz, Austria, where Gustav Mahler, Giacomo Puccini, Arnold Schoenberg, and Alban Berg gathered for the Austrian premiere of Strauss’s scandalous opera Salome—possibly alongside a seventeen-year-old Hitler in the cheap seats.

From that single evening, Ross traces how Wagner’s revolutionary vision of total art metastasized from aesthetic movement into political ideology. From Bayreuth’s temple to Gesamtkunstwerk to the Third Reich’s appropriation of that totalizing vision. The book shows how disagreements about musical form became culture war, then actual war.

Alex Ross’s Wagnerism is 800 pages tracing how one composer’s aesthetic vision became a cultural contagion that infected everything it touched. Ross follows Wagner’s influence from French Symbolist poets like Baudelaire (who heard Tannhäuser and rewrote his entire understanding of art) through T.S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, and D.H. Lawrence, all the way to Hitler occupying the Wagner family box at Bayreuth as honored guest.

The book makes clear that Wagner’s seductive brilliance and his catastrophic legacy aren’t separate phenomena—they’re the same thing. The totalizing vision that produced Tristan also produced the ideology that the Nazis weaponized. You can’t celebrate one without confronting the other.

Christopher Clark’s Revolutionary Spring: Europe Aflame 1848-1849 reconstructs the year when revolution swept across Europe—Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Prague, dozens of smaller cities erupting simultaneously in liberal revolt against conservative monarchies.

Wagner wasn’t just composing during this moment. He was on the Dresden barricades in May 1849, distributing revolutionary pamphlets, conducting revolutionary songs, printing anarchist manifestos while simultaneously working on Lohengrin.

Clark shows how Romantic artists believed aesthetic revolution and political revolution were inseparable—that transforming art meant transforming society. The revolutions failed. But the idea that culture and politics are one didn’t die. It metastasized.

The film would draw from all of these books, but the real source is the music itself.

The Romantic Question

My New Romantic Cinema piece argued that contemporary film is rejecting algorithmic thinking for human-scale moral complexity. That love, goodness, and grace cannot be systematized. That when you try to optimize art, you kill it.

The War of the Romantics was about exactly this question:

Can art transform society through totalizing vision? Or does that path lead to catastrophe?

Wagner believed art powerful enough to transform society. Total artwork—Gesamtkunstwerk—synthesizing music, drama, visual spectacle into overwhelming experience that would remake German culture.

Brahms represented the humanist, liberal tradition. He believed some truths must be protected from ideology. That absolute music—existing for its own sake, not serving extramusical programs—preserved space for human complexity that resists political capture.

I’ve spent the last year building a classical collection1. I own Wagner scores and Brahms symphonies. Strauss’s Salome and Mahler conducting Wagner. De Sabata’s Tristan and Klemperer’s Fidelio.

The more I listen, the more I understand: This was the first and most important culture war. And we’re still living in its wreckage.

The War of the Romantics created the cultural conditions that made WWI and fascism possible.

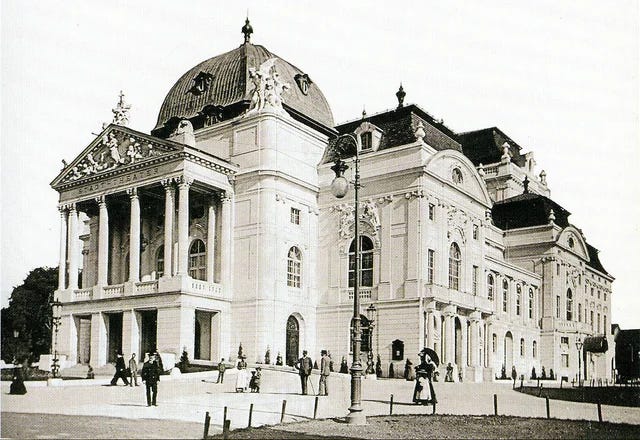

The Opening: May 16, 1906

The film starts without context. No titles. No names. Just image:

A spring evening in provincial Austria. Crowds gather outside the Graz Opera House. We follow a thin seventeen-year-old boy in a cheap suit. He’s borrowed money from relatives to afford this ticket. He looks out of place among the elegant patrons. We never see his face clearly.

Inside, he finds his seat in the upper gallery. Around him, luminaries settle in: Gustav Mahler and Alma in a box. Giacomo Puccini studying his program. Arnold Schoenberg with his students, including Alban Berg.

Richard Strauss appears at the podium. Raises his baton.

The orchestra launches into Salome—those opening bars that sound like moonlight curdling into poison.

The camera pushes slowly toward the boy. His face catches stage light. Rapturous. Transformed.

As the music swells—

SMASH CUT TO:

Dresden Burns

Smoke. Gunfire. Cobblestones torn up for barricades. Bodies in the street.

Young Richard Wagner—mid-thirties, wild-eyed—stands atop a barricade distributing revolutionary pamphlets between conducting revolutionary songs.

This is May 1849. The uprising is failing. Wagner believes German opera can midwife political revolution. Art and politics are inseparable. “The Artwork of the Future!” he shouts over gunfire. Total transformation.

Soldiers advance. Wagner flees through burning streets as Dresden falls.

CUT TO:

Into the Rhine

Winter, 1854. A gaunt Robert Schumann staggers through snow toward the Rhine. He’s hearing music—fragments, obsessive, tormenting. The opening of what will become Brahms’s D Minor Piano Concerto, circling endlessly in his tortured mind.

He reaches the bridge. Throws himself into the freezing water.

The music—that tortured, beautiful melody—plays over his descent.

Fishermen pull him out. He’ll live two more years in an asylum before death releases him.

FADE TO BLACK.

TITLE CARD: THE WAR OF THE ROMANTICS

The film moves between three periods:

1850s-1860s - How Brahms inherits Schumann’s mantle and Wagner builds his vision from exile

1870s-1880s - The camps harden, manifestos fly, critics choose sides, careers are destroyed

1890s-1906 - Both men dead, their disciples fight the final battle as Europe careens toward catastrophe

The music must be the protagonist.

When we see Brahms compose, we watch him physically wrestling with structure. Twenty-one years on his First Symphony because Beethoven’s shadow terrifies him. The camera stays on his hands—powerful, precise, imposing order on inspiration.

When we see Wagner compose, he’s possessed. He paces, sings all the parts, conducts invisible orchestras. His wife Cosima transcribes frantically. The camera whirls around him—he’s channeling something, not crafting it.

I want massive conducting sequences. Eight minutes of Brahms’s First Symphony premiere at Karlsruhe, November 1876. Full orchestra. Period-accurate hall. Otto Dessoff on the podium.

We watch the musicians’ faces showing the athletic difficulty. We see Clara Schumann in the audience—the woman Brahms loved but could never have, watching him honor her dead husband’s legacy. We see critics scribbling. We see Brahms terrified in the wings.

The music is ferociously Classical but underneath, Romantic feeling threatening to burst through. The finale arrives like a dam breaking. Twenty-one years of wrestling with Beethoven’s shadow, resolved in forty-five minutes of architectural triumph.

Then the matching sequence: Hans Richter conducting Götterdämmerung at Bayreuth that same summer.

The orchestra is twice the size. The audience sits in darkness—Wagner’s innovation. Wagner himself is stage director, watching from the wings as his vision consumes the world. Five hours of mythic German legend through chromatic harmony that dissolves tonality itself.

When the Rhine overflows and Valhalla burns, I want the audience in that theater to feel the world ending.

A Love That Couldn’t Be

The emotional core of this film is Brahms and Clara. Their impossible love. The restraint that defined both his life and his music.

Clara Schumann is one of history’s greatest pianists. Robert’s widow. The woman Brahms loved from the moment he met her when he was twenty and she was thirty-four. He never married. She never remarried. For forty years, they orbited each other—too close to separate, too constrained by propriety and memory to unite.

I need a scene—1854, just after Schumann’s suicide attempt—where young Brahms visits Clara. Robert is in the asylum. She’s pregnant, abandoned by most of “polite society.” Brahms is helping manage the household, giving piano lessons to support them.

Late evening. Clara at the piano, playing Robert’s Kinderszenen. She stops mid-phrase, unable to continue. Brahms enters, stands in the doorway. After a long moment, he sits beside her at the bench. Starts playing the piece from where she stopped. She joins him. Four hands, one keyboard.

When they finish, their hands rest side by side on the keys. Neither moves. The moment stretches. Then Brahms stands abruptly and leaves. Clara watches from the window as he walks into the rain.

Restraint that becomes his aesthetic principle.

Later—1860s, Clara’s parlor—Brahms brings her his D Minor Piano Concerto. The one built from those tormented fragments that plagued Robert, salvaged and transformed. She plays through the opening movement while he watches her hands, her face.

She’s the only person who fully understands what he’s attempting—salvaging beauty from Robert’s madness while maintaining architectural control. When she finishes, they sit in silence. The music has said what neither can speak aloud.

Clara hated Wagner’s music. Found it overwrought, indulgent, bombastic. Theater masquerading as symphony. She called Tristan und Isolde “the most repugnant thing I have ever seen or heard in all my life.” Where Wagner demanded attention, Brahms earned it through architecture and restraint. Where Wagner’s music screamed its emotions, Brahms’s music contained them—barely.

I want a scene—1880s, Clara’s last years—where she’s playing through Brahms’s late Intermezzi.

These pieces are different from his earlier work. More willing to admit sadness, uncertainty, the accumulation of decades of unspoken feeling.

Brahms visits. Stands in the doorway, exactly as he did thirty years earlier. Clara plays without turning, but she knows he’s there. Has always known. When she finishes, she finally looks at him. The weight of forty years visible on both their faces. Everything that was never said hanging in the air between them. His late music, melancholy without despair, has finally learned to express what his early works could only contain.

Their love story is the hidden architecture beneath all of Brahms’s music. The restraint that defines his aesthetic came from years of loving someone he couldn’t have. Building prisons beautiful enough to live in.

The Double Concerto

Joseph Joachim is history’s greatest violinist. Jewish. Starts as a Wagnerian, championing Liszt and the “Music of the Future.” Then he hears Brahms and everything changes.

1860: He co-signs a public manifesto attacking Wagner’s school. It’s the declaration of war. Liszt never speaks to him again. His career in Wagner’s circles ends instantly.

Joachim converted to Protestantism in 1855. Critics still hear “Hebrew intensity” in his playing. His mentor Ferdinand David—also Jewish, also converted—warns him about trying to escape through excellence, that they’ll always hear what he’s trying to hide.

Later, Joachim quits his position at the Hanover court in 1865—protesting when another Jewish violinist is denied advancement despite Joachim’s own conversion having exempted him from such discrimination. He composes his Hebrew Melodies for viola and piano, music that acknowledges what he tried to hide.

In 1878, Brahms writes his Violin Concerto specifically for Joachim. It becomes one of the greatest violin concertos in history. Joachim contributes revisions, writes the famous cadenza for the first movement.

They perform it together—Brahms conducting, Joachim as soloist. Their artistic partnership at its absolute peak.

Six years later, everything falls apart.

Joachim’s marriage collapses in the 1880s over paranoid jealousy. He’s convinced his wife Amalie is having an affair with Brahms’s publisher. Brahms sides with her, writing a sympathetic letter that ends up as evidence in the divorce proceedings. Thirty years of friendship, destroyed.

Years later, Brahms writes the Double Concerto specifically for reconciliation.

I want that premiere performance filmed in a single take. Seven minutes. Summer 1887. Camera moving between Brahms conducting, Joachim’s hands on the violin, cellist Robert Hausmann, their faces. The music weaves the violin and cello together—sometimes in harmony, sometimes in tension, finally in resolution.

Forty years of friendship. Four years of silence. Seven minutes of reconciliation.

Wagner as Doctor Doom

Jack Kirby understood something about villainy that most comic book artists didn’t: the best antagonists operate on operatic scale.

Watch Kirby’s panels from the 1960s—Galactus consuming worlds, Darkseid reshaping reality, Doctor Doom remaking Latveria according to singular vision. These aren’t bank robbers. These are gods forcing existence itself to bend to their will. Kirby’s visual language was pure Wagner: overwhelming cosmic spectacle, characters speaking in mythic declarations, every panel building toward apocalyptic synthesis.

Kirby had absorbed the same 19th century Romantic tradition that produced Wagner. His villains don’t just want power—they want to remake reality according to totalizing aesthetic vision. They believe they’ve seen the only possible future and possess the will to force everyone into it.

Marvel borrowed Wagner’s Ring mythology wholesale. Thor’s entire existence is Wagner translated into four-color panels—Asgard, Ragnarok, the Twilight of the Gods reimagined as superhero cosmology. The All-Father Odin making deals that doom his children. Loki sowing chaos. The eternal cycle of gods destroying themselves through their own pride.

But Doctor Doom is the character who most embodies what we might call the Wagner Problem: What happens when a brilliant mind with genuinely revolutionary vision becomes convinced that only totalitarian control can save civilization?

Doom has seen the future—every timeline where he doesn’t rule ends in catastrophe. His totalitarian control becomes, in his mind, morally necessary. He’s not wrong about the threats to human survival. He’s catastrophically wrong about the solution. The certainty that his vision alone can save us becomes the very thing that dooms us.

Wagner believed he’d seen the future of art—total synthesis, overwhelming experience, German culture remade through revolutionary opera. He wasn’t wrong about art’s transformative power. His operas genuinely are revolutionary. He IS a genius.

But like Doom, he’s blind to what happens when totalizing vision becomes totalizing control. When aesthetic revolution detaches from moral restraint. When one brilliant mind decides he’s seen the only possible future and builds institutions to enforce it.

I want a scene—1860s, Swiss exile—where Wagner holds court. The setting should feel like Doom’s throne room—a brilliant mind surrounded by disciples, utterly convinced of his own rightness. Disciples surround him: Franz Liszt (his father-in-law and chief apostle), Hans von Bülow, others.

Von Bülow—who secretly respects Brahms—tries to defend him. Wagner interrupts, warming to his subject. This is him seeing all possible futures, convinced only his path leads to salvation. Art that refuses to engage with power is cowardice dressed as purity.

The Artwork of the Future will synthesize all arts into total experience that transforms society. That’s what he’s building at Bayreuth. That’s what German culture needs to survive.

Von Bülow quietly asks what happens if that power gets misused. Wagner waves this away with the same certainty Doom shows dismissing warnings about Latveria. The only danger is insufficient vision. Art powerful enough to transform society is exactly what we need.

Wagner is partially correct. Art does have transformative power. His operas are genuinely revolutionary.

But like Doom convinced his tyranny saves humanity, Wagner never considers what happens when totalizing artistic vision becomes political ideology. When the dream of total art becomes the nightmare of total control.

The tragedy is that Wagner’s disciples—Mahler, Strauss—would achieve the synthesis he dreamed of.

Salome’s Kiss

As we move into the 1890s, both Brahms and Wagner are dead. But their war spawned the next generation: Mahler (Brahms’s protégé absorbing Wagner’s maximalism), Strauss (Wagner’s heir pushing chromaticism to its limit), Schoenberg (who will soon shatter tonality entirely).

All of them are in Graz that night in 1906.

The Salome sequence needs to be brutal. Strauss has weaponized Wagner’s techniques. The music is violent, erotic, overwhelming. We see:

Mahler recognizing Wagner’s revolution fulfilled in ways even Wagner couldn’t imagine

Puccini realizing Italian opera is obsolete

Schoenberg understanding tonality has reached its breaking point

And throughout: the boy in the cheap seat, absorbing every note of the Dance of the Seven Veils and its gruesome aftermath.

We intercut with Europe’s near future: Franz Ferdinand’s assassination, WWI trenches, the Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler at Bayreuth in 1933.

The final shot: The performance ends. The boy stumbles out into the spring night. We finally see his face clearly as he walks past a poster for the performance.

His reflection in the glass shows us who he is: Adolf Hitler.

The boy who borrowed money from relatives to witness Wagner’s vision made flesh. Who absorbed the idea that art should overwhelm, transform, dominate. Who learned that totalizing aesthetic vision could become totalizing political power.

Wagner’s future realized—not through art saving civilization, but through art justifying its destruction.

FADE TO BLACK.

95 recordings and growing. Multiple versions of the same works because interpretation matters - which is what I tell my wife when the records show up

Utterly brilliant; thank you for this, Doug!

I hope a film film about the War of the Romantics gets made. You need some Lisztomania in there though! Great read.