The Mask and the Mirror

Marathon Man and The Ballad of Wallis Island and Identity, Survival, and Authenticity

Editor’s Note: Geoff Wolinetz returns with his most unexpected pairing yet: Marathon Man (1976) and The Ballad of Wallis Island (2025). After examining performed identity in LA through Albert Brooks and Steve Martin, then exploring solitude as performance in Grey Gardens and Marcel, he’s drilling down to the core question—when does hiding who we are keep us safe, and when does it slowly destroy us?

Written from that liminal space between his New York and LA lives, this piece understands sometimes the mask is survival, others suffocation. - D.H.

“Who am I? Why am I here?”

That’s me quoting Admiral James Stockdale kind of flippantly. He was the butt of a lot of jokes in 1992 when he was Ross Perot’s running mate in the presidential election and made the ultimate American societal sin - giving a poor performance on TV. Stockdale was making a joke about anyone watching even knowing who he was, in spite of his military service and his credentials.1

Those are questions that are worth asking and revisiting all the time for a lot of reasons. The answers to them can change pretty dramatically over time. And honestly, sometimes where we are isn’t the right place to get us to where we want to go. Why am I here literally can be a pretty fascinating question.

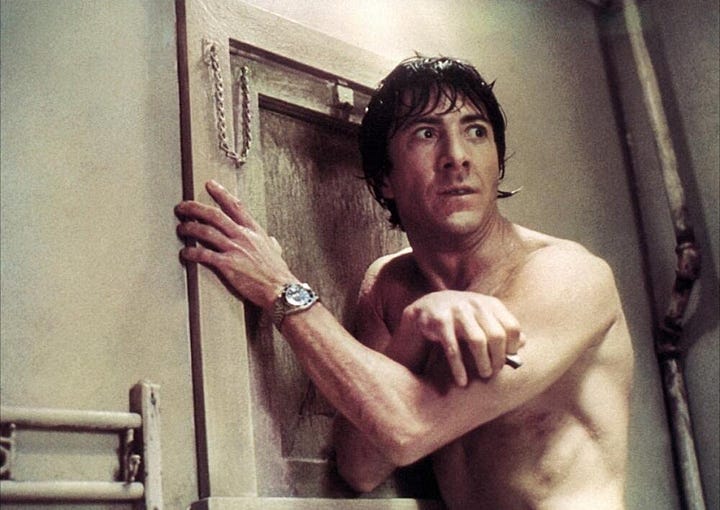

When I’m in New York, I walk by the building where Dustin Hoffman’s character Babe in Marathon Man lives (it’s down the block from my apartment), so I have the opportunity to think about that movie a lot. And since identity - true identity - is such a central theme of that movie, it naturally gets me thinking about matters of identity: who I am, who I want to be and so forth.

And on my way back to Los Angeles, in a weird stroke, the person next to me turned on a movie that I’d never heard of called The Ballad of Wallis Island, so I watched it also. And in another weird stroke, the notion of who we were, who we are and who we want to be is pretty central to that movie.

As it tends to do, my brain took the ball and ran with the theme of identity and self between the films. When you take them together, a really interesting paradox emerges: sometimes we have to hide our identity to survive and sometimes we need to reveal it to truly live.

Marathon Man and Masks

Babe Levy2 is a character with his feet firmly planted in two different worlds: a man with one foot in the world of academia and the other on the running track. On the surface, he’s a quiet graduate student methodically researching McCarthy-era blacklists, living a life defined by books and long-distance runs through Central Park. But under that surface lies another Babe: the son of a disgraced father whose death was tied to the very witch hunts Babe obsesses over. He runs not only to stay fit, but as a means to escape to outrun a past that still shadows him.

But once the plot erupts into violence, his ability to obfuscate who he actually is becomes Babe’s most essential skill. When his brother is murdered and he’s drawn into a web of stolen diamonds and Nazi war criminals, Babe’s survival hinges on his ability to hide who he is, what he knows, to play dumb when pressed, and to maintain a preternatural calm under torture. His ignorance (real at first, later feigned) is his shield. He wears it like a mask, buying time until he can piece together what’s happening and act accordingly.

And to contextualize this even further, the narrative of hiding and performance fits the mood of the era in which the film was made. Marathon Man is a product of 1970s American cinema, steeped in Cold War paranoia and post-Watergate disillusionment.3

It’s a world where identity is dangerous, knowledge is incriminating, and trust is a luxury no one can afford. In Marathon Man, everyone is performing: the government agent, the Nazi fugitive, even Babe himself. The mask is not a choice. In a world built on secrets, it’s a means to fight and a means to protect and the only way to stay alive long enough to find and face the truth.

The Ballad of Wallis Island and Mirrors

And if Marathon Man is about the mask we wear to survive, The Ballad of Wallis Island4 is about the mirror we finally dare to face. At the heart of the film is Charles’s gradual journey back to himself. His character begins untethered, disconnected from any purpose after the death of his partner and from the emotional core that once defined him.

Wallis Island becomes the crucible where that change happens and it is only in this quirky, remote in-between place that Charles allows himself to confront who he has been and who he still wants to be. His transformation is quiet but profound: a slow peeling back of layers until what remains is not someone new, but someone finally seen.

While Charles’s story is quiet, the film’s real masterstroke is in the very loud, very uneven evolution of Herb McGwyer. Herb is the story’s most dramatic embodiment of identity rediscovery. He arrives on the island as an artist desperate to stay relevant, chasing trends that feel hollow, creating work that is clever but bloodless. His tattoos are tools for him to physically change his appearance in pursuit of relevance. Even his name is part of the act.

Herb McGwyer is a persona designed to be marketable, detached from the small-town boy named Chris Pinner who once made art out of necessity rather than for an audience. Over the course of the film, Wallis Island forces him into confrontation with his past and with Charles, who refuses to play along with Herb’s posturing.

The turning point is subtle but unmistakable: Herb stops running from who he is, from Chris Pinner. And in reclaiming his real name, he reclaims the work that once made him whole. The remote and disconnected from the mainland setting is crucial here. It’s like a mythic exile, stripping him of the noise and demands of the outside world until only his true self remains. By the end and over the credits5, Chris Pinner is making art that is raw, vulnerable, and (most importantly) authentic.

Where Charles’s arc is about finding the courage to be present, Chris’s is about finding the courage to be true. Their evolutions mirror each other. Both men come to understand that the cost of denying the self is too high. If Marathon Man insists that the mask is a survival mechanism, Ballad reminds us that keeping it on too long risks suffocation. Its central argument is that there is a life beyond performance, but you can only live it once you are willing to let the mirror show you who you really are.

The Paradox of Identity

The mask vs. the mirror - what do we hide vs. what do we show. That’s the central way these films explore the notion of identity. Both Marathon Man and The Ballad of Wallis Island circle the same paradox: hiding keeps us safe but isolates us, while revealing frees us but carries risk.

Babe begins Marathon Man behind a mask. He’s a quiet graduate student, running laps as if he can outrun the ghost of his father. But when the repeated question “Is it safe?”6 pops in the Szell torture scene, that mask is violently stripped away and forces Babe to confront not just the pain he tried to evade his entire life but his own capacity for resistance.

What follows is transformation: Babe sheds passivity. He fights back. And he claims a new active identity forged in choice rather than a passive one based in fear.

In Ballad of Wallis Island, the protagonists wear a different kind of mask. It’s a mask crafted from denial and self-preservation. Haunted by past choices, they try to keep their history buried, presenting a curated version of themselves to the world. For Charles and Herb, however, the island becomes a mirror, forcing them to confront what they’ve hidden for so long.

Each interaction peels back a layer of that mask. A casual conversation over dinner, for instance, might suddenly turn when an offhand remark dredges up a memory they’ve both tried to forget, leaving them exposed and vulnerable. The act of facing these truths is dangerous: it puts their relationships, their sense of self, and their carefully constructed facades at risk. Yet in that very risk lies freedom. By the end, they are no longer simply surviving behind disguises; they are living honestly, even if it costs them.

Together, these arcs show that identity is situational. Sometimes we survive by suppression, wearing the mask. Other times, survival requires expression: stepping into the mirror, accepting the risk, and becoming someone new.

What These Stories Tell Us About Us

Of course, we don’t live on Wallis Island or in the 1970s New York of Babe Levy, but the masks worn by the characters in both films feel instantly familiar. In daily life, we put on our own masks more than once every day: the professional persona in the office, the curated identity projected across social media, the carefully edited story we tell at parties.

These masks are not lies or even intentionally false. Each one serves a specific purpose: they help us navigate social expectations, protect vulnerabilities, and even open doors for us. Living authentically is amazing, but in many cases and many ways, it’s both aspirational and really challenging.

The culture we live in, shaped by surveillance, digital permanence, and relentless scrutiny, can make the cost of dropping the mask feel impossibly high. Do we risk too much by allowing ourselves to be fully visible, with all of the warts and scars that make us human?

On the other hand, there is a different danger in never stepping into the mirror, never facing what lies beneath. To live only through projection is to let the mask harden into the face itself, which has a whole host of other challenges.7

Together, these two films offer complementary lessons. Marathon Man warns us of the dangers of exposure. Sometimes concealment is survival. Ballad of Wallis Island, in contrast, suggests that freedom can only come from stripping away the façade.

And as usual, the truth almost certainly lies somewhere between: to live well, we must learn the balance of knowing when to guard our identities against a world that would exploit them, and when to claim them fully, even if doing so feels risky.

That tension is where authenticity, and humanity, resides.

Living Between Mask and Mirror

The question of who we are is never simple. Identity can be both shield and revelation, a way of protecting ourselves from the world and a way of declaring who we are within it.

The characters in these films remind us that wearing a mask can be necessary. It allows us to survive, to maneuver, to keep parts of ourselves intact. To cope. Yet they also show that the mask becomes a prison when worn too long, keeping us from the freedom that only being true to our authentic selves can bring.

We live that same paradox every day. To reveal ourselves completely may feel reckless, but to hide indefinitely is to erode the very self we’re trying to preserve. So the question lingers: are you wearing the mask because you must or are you wearing it because you’re afraid of the mirror?

It was actually a pretty good joke too. He got a nice laugh.

Go look up how old Dustin Hoffman is. I’ll wait. He’s like 10 years older than you thought he was, right?

I wanted to make a historical note about American politics here, but instead I’m going to talk about John Schlesinger - the director of this film who fought for the British in World War II and won the Academy Award for directing Midnight Cowboy, which means he directed Dustin Hoffman in two of his, let’s say, top five roles. Hoffman paid tribute to Schlesinger when he died in 2003 by saying “he loved actors more than anyone I ever worked with.”

The movie has a lot going for it, but if you’re on the fence, I can tell you that Carey Mulligan is in it and it’s only 99 minutes long, which means if you’re like me, you can actually watch it in one sitting

The song that plays over the credits absolutely slaps. 10/10 no notes

I was at bar trivia once like 25 years ago and the question was “What is the three word phrase that Laurence Olivier says in Marathon Man?” And I rang in and screamed “IS IT SAFE?” And the guy running the trivia said, “It is for the other guy. He rang in first” and I lost by one question and in case it’s not clear, I’m still upset

While we’re talking about masks, there’s an absolutely stellar late run episode of the Twilight Zone, called “The Masks” that uses Mardi Gras masks as a central plot device.