The Last Romantic: Josef Von Sternberg and the Architecture of Sound

From Wagner’s Bayreuth to Hollywood’s sound stages—how early cinema achieved the dream of total art - a response to the latest Filmstack challenge.

In Swabreen Bakr’s FilmStack prompt, she wisely asks us to explore “how key moments of sound usage helped shape a scene or contributed to the emotions you had while watching it.”

The highly underrated, early Hollywood filmmaker Josef Von Sternberg offers us all a masterclass in using sound as architecture—building spaces, emotions, and meaning through total sonic control, where every whisper, every silence, every rhythm becomes part of the cinematic opera.

In Von Sternberg’s first sound film—The Blue Angel (1930), when the increasingly debauched Professor Rath closes the door to Lola-Lola’s dressing room, the cabaret music doesn’t fade—it vanishes. A complete acoustic cutoff. The sudden silence hits like a slap, transforming a cluttered backstage space into a confessional.

His films are the bridge between the fin de siecle Ringstrasse in Vienna and Hollywood Boulevard, proving that cinema could achieve opera’s condition: total art where every element sings.

From Wagner’s Vienna to Fort Lee: The Craftsman’s Education

Von Sternberg, born Jonas Sternberg in Vienna in 1894, carried the 19th century’s operatic sensibility into the 20th century’s newest art form. In Vienna—where Mahler was revolutionizing opera, where every gesture in the Staatsoper meant death or transcendence—young Sternberg absorbed the idea that drama isn’t about words but about musical structure.

This was the Vienna still reverberating from the War of the Romantics—that bitter 19th-century battle between Wagner’s camp (who believed in Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art) and Brahms’s conservatives (who championed absolute music). Wagner1 had dreamed of unifying music, poetry, drama, and visual art into a single overwhelming experience.

Von Sternberg breathed this air. He understood instinctively what Wagner had preached: that art’s highest calling was synthesis, not separation. von Sternberg would achieve his Gesamtkunstwerk through absolute control of every sonic element. Every footstep, every door slam, every breath would be as carefully orchestrated as Wagner’s leitmotifs.

When Hollywood panicked about sound destroying cinema’s visual poetry, Von Sternberg understood something his native American colleagues didn’t: he’d been making operas all along.

Von Sternberg was a craftsman, and very much a model for today’s NonDe2 film scene. He spent the early years of his career working in the Fort Lee, NJ studios - learning how to process, edit, cut and shoot film. Cleaning and patching film stock by day, working as a projectionist by night—watching films backwards as he rewound reels, understanding cinema as rhythm and repetition.

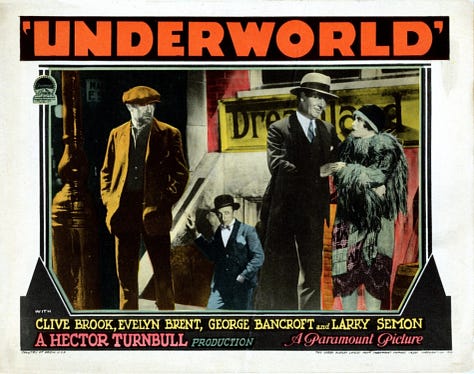

This craftsmanship is seen in every frame of Underworld (1927) and The Last Command (1928), his silent masterpieces. These films are clear early examples of Von Sternberg adapting operatic production, framing and staging for the big screen.

The German Exodus and Hollywood’s Gain

Von Sternberg wasn’t alone in bringing Germanic sensibilities to Hollywood. He was part of a larger exodus—Ernst Lubitsch arrived first, bringing his “touch” to sophisticated comedies. Karl Freund, who’d shot The Last Laugh for Murnau, revolutionized Hollywood cinematography. Max Ophuls would perfect the moving camera as emotional expression. Robert Siodmak and Billy Wilder would help birth film noir from German Expressionist shadows.

All carried a cultural tradition that stretched back through Wagner to the German Romantics. They understood that cinema, like opera, could be a total art form. Taking cues from Wagner’s leitmotifs—musical themes representing characters or ideas—they used visual motifs, lighting patterns, camera movements along with the sound.

But before sound was added to film, Von Sternberg was already thinking musically.

In Underworld, George Bancroft’s gangster Bull Weed moves through speakeasy scenes with such rhythmic precision that you can practically hear the jazz. The film’s visual crescendos—the flower shop murder, the violent climax, the death scene—play like Verdi arias, all gesture and emotion building to inevitable tragedy.

Underworld creates much of the visual poetry we associate with film noir, and darker early comic strips3 like Batman and the Phantom.

The Last Command pushes this even further. Emil Jannings’s fallen Russian general performs what can only be called a Boris Godunov in miniature—a tragic arc from power to madness rendered “fresh, brutal and relevant” through pure visual music. The film’s flashback structure creates arias interrupting present-tense recitative.

Von Sternberg used music on set to guide his actors’ rhythms, understanding that cinema was temporal art like music, not spatial art like painting. When sound arrived, he didn’t have to adapt—he just had to let us hear what had always been there.

From Silent Arias to Sound Symphonies

That door-closing moment in The Blue Angel (1930) helped revolutionize film sound just three years into the talkie era. While other directors were still figuring out where to hide microphones, Von Sternberg was creating total sonic environments—every element controlled, every transition meaningful.

When the door opens, Friedrich Hollaender’s “Falling in Love Again” floods in with the smoke and chaos of the cabaret. When it closes, we’re trapped in suffocating intimacy with the Professor’s desire. This isn’t just realistic sound—it’s architectural sound, building psychological spaces.

But the film’s most devastating sound moment comes at the end. As Professor Rath performs his humiliating clown act, dying on stage while crowing like a rooster, the cabaret audience’s laughter transforms from entertainment to grotesque mockery. The laughter becomes monstrous, almost inhuman, as we watch a man’s complete degradation.

Filmed just months before the Nazis took power, the laughing takes on ominous, darker tones. All of bourgeois society is degraded and mocked by a new generation that is steeped in cruelty.

This is pure opera—the tragic hero’s death aria replaced by animal sounds and cruel laughter, grandeur inverted into cabaret hell. Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk achieved through total sonic control.

The Train That Taught Actors How to Speak

“This is the Shanghai Express. Everybody must talk like a train.”

Von Sternberg’s direction to his actors in Shanghai Express (1932) reveals von Sternberg’s total approach to sound. Listen to how Marlene Dietrich delivers “It took more than one man to change my name to Shanghai Lily”—her cadence matches the locomotive’s rhythm exactly. Clive Brook’s clipped British responses provide counterpoint. Even the supporting characters speak in patterns that echo the train’s mechanical percussion.

This is Wagnerian totality applied to dialogue—every word timed to the mechanical heartbeat of the train. Sound engineer Harry D. Mills captured every detail. The clack of train tracks or footsteps or shutter being slammed shut creates total immersion. The entire sonic environment becomes an organism, with human speech just one element in the larger composition.

Listen to the rhythms of speech in the below scene. Each character’s dialogue is in complete syncopation with the jazzy score, and the train’s motion. Von Sternberg had discovered something profound: mechanical sound could structure human emotion, creating a total sonic architecture where every element depends on every other.

Again the commitment to total art—learned in Vienna, built in Fort Lee, perfected in Hollywood.

The Drums of Colonial Desire

In Morocco (1930), the drums of the Foreign Legion don’t just accompany the action—they become the film’s total sonic environment. The military percussion becomes the film’s heartbeat, its libido, its death march—everything else in the sonic landscape relates to these drums.

This is Wagnerian orchestration in its purest form. Wagner used leitmotifs to create a web of musical meaning; von Sternberg uses drums to create a total sonic world. Watch the scene where Dietrich first sees Gary Cooper. The drums start as military timekeeper but gradually colonize the entire soundtrack.

When she makes her final choice—following Cooper into the desert, kicking off her shoes to join the camp followers—those drums have transformed from one element among many to the total sonic reality. The drums tell us what the characters cannot: that desire has its own marching orders.

What Von Sternberg Heard That We’ve Forgotten

Watching his films in our era of wall-to-wall soundtracks and Dolby Atmos assault, three principles of total sound emerge:

Sound as Total Architecture

Every Von Sternberg film uses sound to build complete worlds. In The Blue Angel, we don’t just hear individual sounds—we experience total sonic environments. The classroom isn’t just chalk and coughing but a complete acoustic space; the cabaret isn’t just music and laughter but a total sonic reality. Modern films add sounds; Von Sternberg built worlds.

Rhythm as Total Control

The “Shanghai Express” principle—dialogue, effects, and music all submit to a master rhythm. Maximalism through control. Every sonic element serves the larger rhythmic structure. Contemporary directors layer sounds; von Sternberg orchestrated them into unified wholes.

Silence as Active Element

In von Sternberg’s total sound design, silence isn’t absence but presence—another color on the sonic palette, carefully deployed and controlled. These silences create dramatic weight, functioning as powerfully as Wagner’s orchestral climaxes. Modern films fear silence; von Sternberg made it sing.

Lessons for Today

Swabreen Bakr asked us how sound shapes emotion in cinema.

Von Sternberg’s answer: by creating total sonic worlds where every element—from dialogue rhythm to footstep echo to strategic silence—works in concert. His films don’t tell you what to feel through musical cues. Instead, they immerse you in complete sonic environments that generate authentic emotion through their totality.

In his films every sound had its place in the larger architecture. Silence roars and whispers overwhelm. Rhythm literally structured reality itself.

Von Sternberg proved that cinema could be the 20th century’s opera—not by adding orchestras but by understanding that film sound could achieve the Wagnerian dream of total art.

He was the last of the 19th century Viennese romantics and the first of the sound film modernists, building a bridge between Wagner’s Bayreuth and Hollywood’s sound stages.

He showed Hollywood that cinema wasn’t illustrated radio plays but a new form of opera—where every sonic element could be controlled, orchestrated, and integrated into a total work of art4.

The German émigrés who followed—Ophuls with his endlessly moving camera creating sonic motion, Siodmak with his noir soundscapes, Wilder with his rhythmic dialogue—all carried pieces of this vision. They understood what the Romantics had dreamed and von Sternberg had achieved: that art reaches its highest form when all elements submit to a total vision.

Wagner dreamed of the Gesamtkunstwerk. Von Sternberg achieved it by making every sound count.

If a new generation of filmmakers is indeed committed to recapturing the humanist, romantic spirit - Josef Von Sternberg’s approach to sound, his approach to total cinema is a great place to find influence.

Richard Wagner is perhaps the most complicated case of Art vs Artist in the past 200 years. I am not going to have THAT discussion here, but Alex’s Ross’s “Wagnerism” is an incredible exploration of Wagner’s genius, his tremendous racism, anti-semitism, hypocrisy, and impact on art and culture

Admittedly, I do not love this branding, but people seem to be using it, so when in Filmstack…

Warren Beatty’s criminally underseen and brilliant Dick Tracy (1990) directly references several scenes in Underworld, as does the Coen Brothers’ Miller’s Crossing (1990). Then again, so does basically every gangster movie made post 1928.

Von Sternberg’s influence extends far beyond film: At UCLA, Von Sternberg taught film students that included future Doors members Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek. Manzarek later called him “perhaps the greatest single influence on The Doors.”

Von Sternberg also taught the future Doors how to see and hear cinematically. No wonder their music feels so visual, so concerned with creating total sonic environments where every element matters. They learned from the master.