Star Trek's Secret Bohemian Origins

How Ikarie XB-1 beat the Enterprise NCC-1701 to the Final Frontier

I first fell in love with Star Trek at seven, sitting next to my father watching old reruns of Kirk and Spock, and the first incredible seasons of "The Next Generation." By my 1989 bar mitzvah, the devotion ran deep enough that my parents indulged me in a Trek-themed celebration. We had big cardboard cutouts made of the original Enterprise and Klingon ships. We gave out "Next Generation" phasers as party favors. It was a nerdy trip.

But through over 40 years of Trek fandom—from the end of the Roddenberry era, to J.J. Abrams' questionable but entertaining reboot films, to the not-so-great "modern Trek" of "Discovery," "Strange New Worlds" and "Section 17", I had no idea that the utopian future I celebrated — humanity overcoming its barbarous nature through science and cooperation — had originated behind the Iron Curtain?

This week, a blind purchase changed my entire perspective on Star Trek and how it was conceived on both a technical and philosophical level. On a lark, I picked up a Second Run DVD of a 1963 Czech science fiction film called Ikarie XB-1. What unfolded wasn't just a forgotten Cold War sci-fi curiosity but a cinematic revelation—I was watching Star Trek's unacknowledged ancestor. The starship interiors, the multinational crew, the episodic cosmic encounters, even the radiation sacrifice that would define The Wrath of Khan—all existed in this film that predated Trek by four years.

FROM STANISLAW TO THE FINAL FRONTIER

While Star Trek emerged from Roddenberry's imagination, Ikarie XB-1 sprang from Polish science fiction master Stanisław Lem. The film adapts his 1955 novel "The Magellanic Cloud," exploring the philosophical implications of first contact with something truly alien—territory Lem would later perfect in "Solaris," which itself inspired multiple film adaptations.

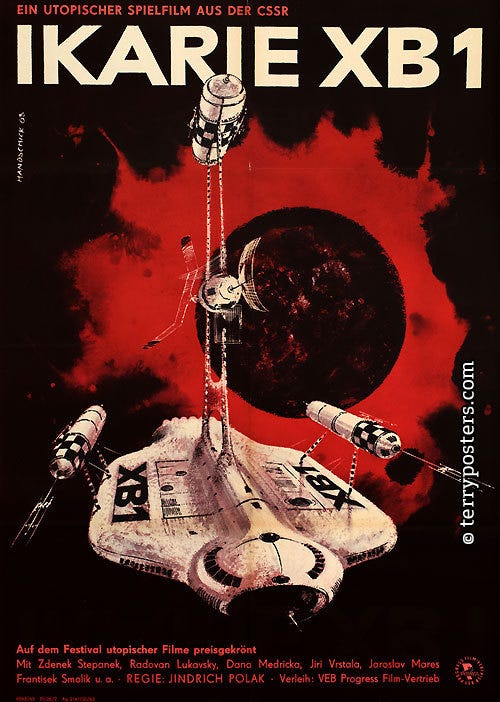

Set in 2163 (not far from Captain Kirk's 23rd-century adventures), director Jindřich Polák's camera follows the starship Ikarie XB-1 to investigate a mysterious "White Planet" orbiting Alpha Centauri. His framing is democratic—consistently using tracking shots that move fluidly between crew members rather than isolating heroic figures.

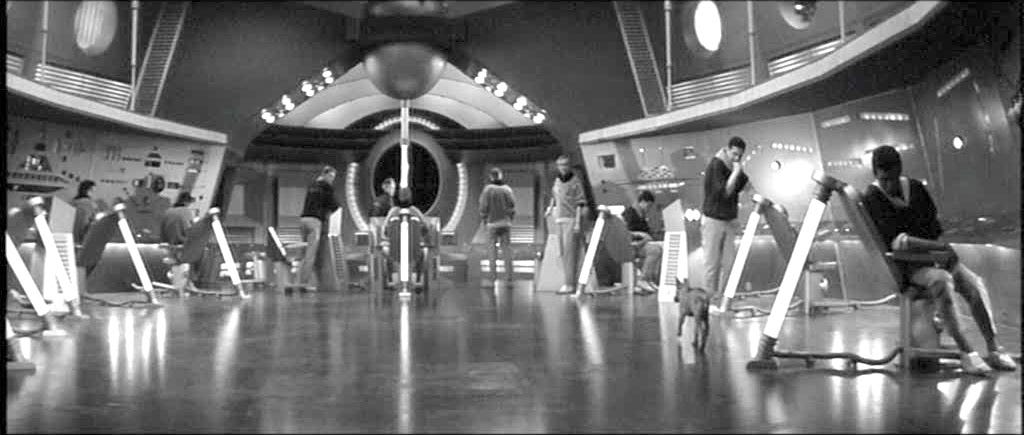

Where American sci-fi typically employed rapid cutting and dramatic low angles to emphasize individual heroism, Polák orchestrates ensemble sequences through patient long takes that distribute agency across multiple characters—exactly what Trek would later do with its bridge crew, from Uhura's communications console to Sulu at the helm to Chekov at navigation.

RARE GLIMPSES OF COLD WAR OPTIMISM

What's striking about Ikarie XB-1 is how its visual language contradicts Western assumptions about life behind the Iron Curtain. Rather than shadows and expressionist angst, cinematographer Jan Kališ employs high-key lighting that creates visual flatness—a democratization of the frame where no character dominates through shadowy emphasis. The society launching the Ikarie has moved beyond national rivalries toward unified human identity. It is literally a Federation prototype articulated through light itself.

This isn't far from how Trek illuminated the Enterprise bridge—bright, even lighting that emphasized transparency and cooperation rather than hierarchy. Even Captain Kirk rarely gets dramatic shadowy emphasis unless he's making a particularly difficult moral choice (think of his face half-lit during "City on the Edge of Forever" as he decides whether to let Edith Keeler die).

Polák arranges his multinational crew in balanced compositions that prefigure the Enterprise's diverse bridge. Both vessels become visual metaphors of integrated futures, with camera movements that emphasize connection rather than hierarchy. This cinematic integration appears even more revolutionary considering it emerged during the Cold War's darkest moments—long before Lieutenant Uhura and Ensign Chekov represented a hopeful multiethnic future on American television.

IKARIE’S KOBAYASHI MARU

Ikarie XB-1 faced its own no-win scenario in America—a situation that would have made Starfleet Academy's infamous unbeatable test look simple. Released as "Voyage to the End of the Universe," American International Pictures committed an unconscionable act of cinematic vandalism. They cut ten minutes, Anglicized character names, and—in a visual perversion worthy of the Mirror Universe ("Mirror, Mirror" anyone?)—completely rewrote the ending.

The Czech original concludes with a revelatory sequence: clouds parting to reveal a gleaming alien civilization, captured in a series of increasingly tighter frames on awestruck human faces. This climactic shot progression creates pure visual philosophy—discovery as transformative experience. The American version replaced this with disembodied stock footage of New York City, implying the alien crew had actually been traveling to Earth—a "twist" that destroyed the film's entire visual argument about human potential.1

This butchered version circulated in Hollywood precisely when Roddenberry was developing Star Trek. While there's no definitive evidence Roddenberry saw it, many film historians believe he must have been exposed to it.2 The visual DNA transfer is unmistakable in everything from lighting schemes to compositional balance—from the way the ship interiors are shot to how the crew interacts with their environment.

SPACECRAFT AS SOCIETY: BEFORE THE HOLODECK

Both Ikarie XB-1 and Star Trek conceive of starships as floating communities, not merely vehicles. What separates them from previous science fiction is their camera's attention to life between crises—what the crew does when they're not battling Klingons or encountering energy beings. Polák's lens lingers on social dynamics, employing deep-focus compositions during a lively dance sequence that keeps every level of the ship simultaneously visible—a direct precursor to Trek's multilevel rec room scenes and later the holodeck where Picard would enjoy his Dixon Hill detective programs.

Zdeněk Liška's modernist electronic score creates a unified sonic environment that refuses traditional character leitmotifs in favor of collective auditory experiences. The music doesn't punctuate heroic moments but creates environmental continuity—an approach early Trek composers would emulate before Alexander Courage's theme became the show's sonic signature.

The circular architecture of both vessels creates visual metaphors for community that the camera exploits through 360-degree movement possibilities. When crisis strikes—whether a dark star or Klingon attack—both works employ rhythmic shot-reverse-shot patterns that distribute problem-solving across multiple characters rather than centralizing it in one heroic figure. Think of how many times a typical Trek episode cuts from Kirk to Spock to McCoy to Scotty during a crisis, each contributing their expertise rather than the captain solving everything alone.

REDSHIRTS AND RADIATION: THE PROTO-EPISODES

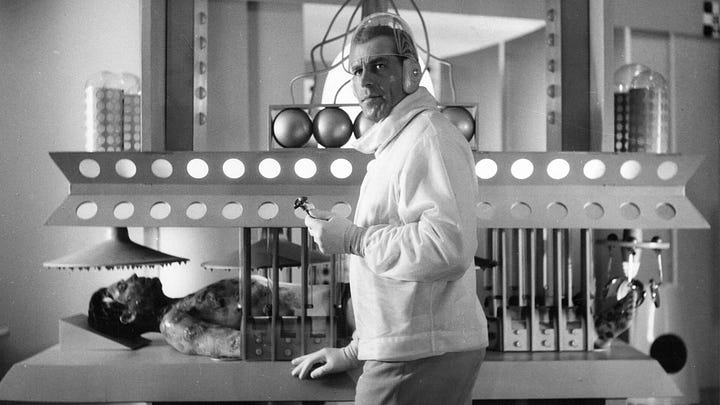

The Czech film presents a series of cinematic set pieces that would become Trek templates: the discovery of an abandoned 20th-century vessel (photographed through disorienting Dutch angles signaling moral decay), exposure to a deadly radioactive "dark star" (visualized through overexposure that gradually consumes the frame), and the psychological deterioration of a crew member (tracked through increasingly fragmented editing).3

These scenarios read like a catalog of classic Trek episodes—finding the S.S. Botany Bay in "Space Seed," encountering the planet killer in "The Doomsday Machine," or watching crew members lose their minds from various space phenomena in episodes like "The Naked Time." Most striking is Ikarie's "doomed away mission" sequence. Polák films the exploration team in protective gear through wide shots that emphasize their vulnerability within the frame, creating visual tension through their containment in hostile space—a framing technique Trek would repeatedly employ for its ill-fated redshirts who never made it back to the transporter room.

"THE NEEDS OF THE MANY": SPOCK'S CZECH ORIGINS

No death in Trek hits harder than Spock's in The Wrath of Khan. What makes this scene so powerful isn't just the loss but its visual grammar—Spock separated by glass from helpless friends, radiation burning him from within as he saves the ship.

This iconic sequence has a direct predecessor in Ikarie XB-1. The Czech film's dark star sequence creates not just a similar narrative beat but an identical visual composition: the sacrificial figure framed through transparent barriers, photographed first in objective master shots establishing physical space, then in increasingly intimate close-ups as life fades.

When Spock tells Kirk that "the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few," he's articulating a philosophy present in Ikarie XB-1 nearly two decades earlier—a moral framework visualized through identical compositional choices across the ideological divide of the Cold War. You almost expect to hear DeForest Kelley's McCoy grumbling, "He's dead, Jim" as the Czech crew mourns their fallen comrade.

WHERE NO ONE HAS GONE BEFORE: BACK TO BASICS

Watching today's Trek offerings—with notable exceptions like Terry Matalas's excellent "Picard: Season 3" that finally brought us the Next Generation reunion we deserved—I can't help but feel a disconnection from the humanistic vision that makes both Ikarie and classic Trek so compelling. Current iterations seem more interested in rewriting existing characters like Spock and Chris Pike than advancing the visual language of human potential that defined the franchise.

Modern Trek has the technical capacity to create stunning visual effects that Roddenberry could only dream of, yet often lacks the philosophical foundation that made the original series so enduring. Where's the sense of wonder? The moral dilemmas? The optimistic vision of humanity's potential? These aren't just themes—they're visual propositions expressed through camera choices, lighting designs, and compositional strategies that both Polák and early Trek directors understood intuitively.

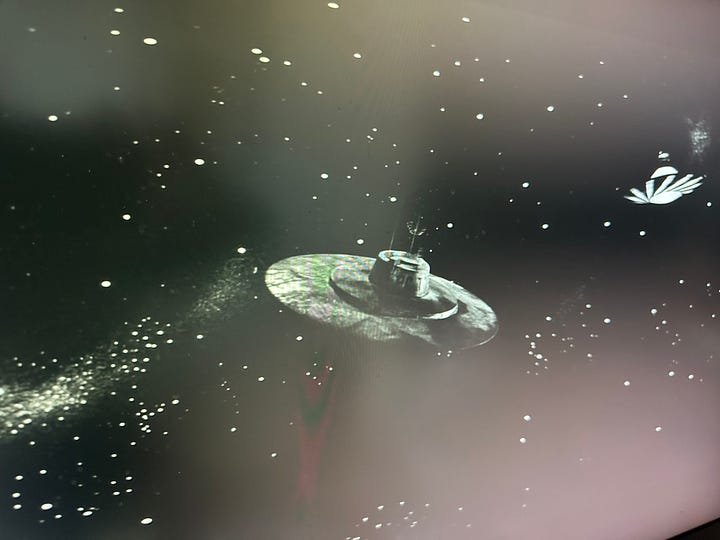

What made both works transcendent wasn't their special effects—which in both productions are fairly crude and utilitarian—but their camera's profound optimism. They created visual systems where diversity became strength, where scientific inquiry paired with ethical consideration, where the frame itself expressed ideals through light, composition, and movement.

It's no wonder that phrases like "to boldly go where no one has gone before" and "live long and prosper" resonate across generations.

Modern Trek producers would do well to study Polák's formal techniques alongside Roddenberry's original vision. When I watch the Czech crew of the Ikarie gazing in wonder at their discovery, I can almost hear the traditional Trek fanfare—bom ba bom—that accompanied similar moments throughout the franchise.

What's remarkable is that Ikarie XB-1's visual fingerprints aren't just all over Trek but also Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey—making this little-known Czech film perhaps the most influential spatial grammar for cosmic cinema most people have never seen.4

As I sat in my living room this week, I felt that rare thrill of genuine discovery. For a Trek fan of nearly forty years, finding this forgotten Czech ancestor felt like coming home to a place I'd never been before. As if Q had shown me an alternate timeline where Trek's origins weren't quite what I'd believed.

The next time I settle in for a Trek marathon, I'll be watching with new eyes, seeing not just Roddenberry's vision but the Bohemian vision of humanity’s future that inspired it all.

To boldly go...

Ikarie XB-1 is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel

You can watch the trailer for the restored Ikarie XB-1 here, and the Second Run DVD offers the definitive restoration with special features.

Here's where you can stream the Star Trek content mentioned in this article as of March 2025:

Star Trek: The Original Series

Paramount+ (primary home with all episodes)

Also available for purchase: Amazon Video, Apple TV, Fandango At Home

Star Trek: The Next Generation

Paramount+ (primary home with all episodes)

Also available for purchase: Amazon Video, Apple TV, Fandango At Home

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan

Kanopy (with subscription)

For all Star Trek content, Paramount+ is the definitive streaming home with the complete library. Other services may have select episodes or temporary streaming rights, but Paramount+ guarantees access to the entire franchise.

According to film critic Glenn Erickson, AIP's edits and script changes were intended to create a gimmicky "surprise" ending, revealing that the Ikarie and its crew have come from an alien world and that the "Green Planet" is in fact Earth

Mehelli Modi, founder of Second Run DVD which released a restored version of the film, states in an interview with Radio Prague International: "It's very clear when you watch Ikarie now that Gene Roddenberry, who was the creator of Star Trek, and Kubrick had seen it. Star Trek was the first American series that talked about a kind of multinational crew and if you look at the uniforms they're very similar, too."

Film historian Jordan Hoffman notes in his article for Birth.Movies.Death that "the episodic nature of a space crew exploring the solar system while still dealing with day-to-day ship upkeep is a signature of Star Trek, and more than a few of the show's episodes resemble the Ikarie XB-1 characters' discovery of a mysterious ship.

Stanley Kubrick reportedly viewed Ikarie XB-1 when screening science fiction films as part of his pre-production research for 2001: A Space Odyssey. His assistant Anthony Frewin confirmed in the book Stanley Kubrick: New Perspectives that Kubrick thought it was "a half step up from your average science fiction film in terms of its theme and presentation."