From the Heart: Dudamel and Lim's American Statement

A cathartic evening of deeply American music

NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC , Gustavo Dudamel, conductor, September 19th 2025 at Lincoln Center, performing Lanzilotti’s of light and stone, Bartok’s Piano Concerto No. 3, and Charles Ives’s Symphony No. 2

Row AA, Seats 101, 102

Since March, Cognitive Frames has practiced democratic criticism for film. Today we expand to live performance.

Cognitive Frames: In the Room covers live performance and cultural events: symphony, opera, theater, concerts, film festivals, art openings—anywhere culture happens in real time.

We know that every perspective illuminates something different. The film student sees techniques the regular subscriber doesn't notice; the subscriber knows the director's journey the student hasn't tracked. Someone's first Broadway show, someone's hundredth time at Film Forum, someone finally trying opera or rediscovering jazz—each viewpoint reveals what others can't see.

We want to cover it all: galleries, readings, dance, anywhere culture lives. Your perspective matters.

Today: Dudamel's opening week at the NY Phil with 21-year-old pianist Yunchan Lim playing Bartók's final concerto.

This fall: The Met's world premiere of Kavalier & Clay, the 63rd New York Film Festival, Jane Krakowski in Oh, Mary!, and much more.

Traditional media criticism might be shrinking. Real conversations about culture are just beginning.

Want to write about something you witnessed? Email us: submissions@cognitivefilms.org

– D.H.

The last time I saw someone this intense playing the piano live was Tori Amos at the Beacon Theater in 1992.

But Bartók's Third Piano Concerto is considerably more complicated than "Cornflake Girl."

That's how 21-year-old Yunchan Lim announced himself Tuesday night at David Geffen Hall—not as the prodigy who became the youngest-ever Van Cliburn winner at 18, but as a rock star (or K-Pop star) that had full command of the stage, the audience and the music.

My brother and I had just come from Sugarfish, properly fortified with salmon and yellowtail, walking down Broadway on one of those perfect September evenings that are one more proof point that New York City is the greatest of all cities.

He's more of a Phish fan—has probably seen them 100+ times—but he's been getting increasingly classical-pilled lately. This performance definitely pushed him further down that rabbit hole.

World-class sushi and sake at 6 and world-class Bartók at 7:30. This is the blessing of New York: everything you could want culturally is a subway ride away, and sometimes it all converges on a single Tuesday night on the Upper West Side.

The Final Performance Energy

This was the last of five performances of Gustavo Dudamel's opening week as Music & Artistic Director Designate. You could feel it in the orchestra—that particular energy of a final performance where everything's been worked out but hasn't gotten stale.

Dudamel programmed an argument about America: Hawaiian composer Leilehua Lanzilotti's world premiere of light and stone, Bartók dying in exile on the Upper West Side, and Charles Ives cramming every American tune he could remember into a symphony that waited fifty years for its premiere.

Let me be clear about something: I am admittedly new to the world of classical music performance. For the last year or so, I've primarily seen the Met Orchestra. They are so, so wonderful.

But the NY Philharmonic under Dudamel is something different. The hype is 100% real.

The Hawaiian Sunrise

Lanzilotti's of light and stone opened the evening—a 15-minute evocation of King Kalākaua's 1888 birthday celebration when he flooded Iolani Palace with Edison's brand-new electric lights. The piece moves through four interpretations of the word "haku": to compose, core (as in stone), to rise up (as the moon), to braid (as a lei).

At times it captured something like the sunrise feeling of Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé. At others, I felt it decomposing into "classical chill" playlist music. Admittedly, this could be my lack of familiarity with the piece. I need to hear it more before rendering any real judgment. But there were undeniable moments—the clarinet's mournful second movement solo, the way the woodwinds braided together in the third like the lei of the title.

The Hungarian in New York

Bela Bartok was dying while writing his Third Piano Concerto. Leukemia. Living blocks from Lincoln Center on the Upper West Side after fleeing Nazi oppression. He managed to finish everything except the last 17 bars of orchestration, which his student Tibor Serly completed. It was meant as a vehicle for his pianist wife to perform and stay financially afloat after his death.

You can hear all of this in the music—the mix of melancholy, excitement, chaos, and beauty he found in New York. Which of course is why Dudamel picked it. This concerto is New York explaining itself to itself. A dying Hungarian exile trying to capture what he heard walking these same streets we'd just walked from dinner.

Lim didn't just play this piece. He inhabited it.

Dudamel and Lim have an obvious and easy chemistry. You could feel their bond particularly during the second movement, the Adagio religioso, which demands a slower, contemplative pace. Lim smoldered through these passages—deeply in conversation with the orchestra and conductor. The normally subdued opening became something sparkling, alive.

The third movement dials the intensity back up with its modernist jangle of chaos. Bartók is very much the Hungarian in New York in this passage. Lim brought both the sparkle and the weight, making each gesture feel both independent and part of the larger puzzle.

Is he the best piano player alive? I am in no way capable of judging that. Did he blow my mind? Hell yeah he did.

He deserved every one of his four standing ovations.

Before finally dashing offstage, Lim played a modest encore—a 19th-century waltz called "This Quiet Summer Night" by Feofil Tolstoy (no relation). After the Bartók, it felt like someone offering you a glass of water after you'd been drinking absinthe.

Ives and the American Story

Charles Ives' Symphony No. 2 was played impeccably.

Ives wrote this piece in the early years of the 20th century, and aside from a few local school performances, kept it in a proverbial drawer while he pursued a highly successful career in insurance. (There's something deeply American about that—our greatest experimental composer selling insurance while sweet, lyrical Brahmsian music poured out of him.)

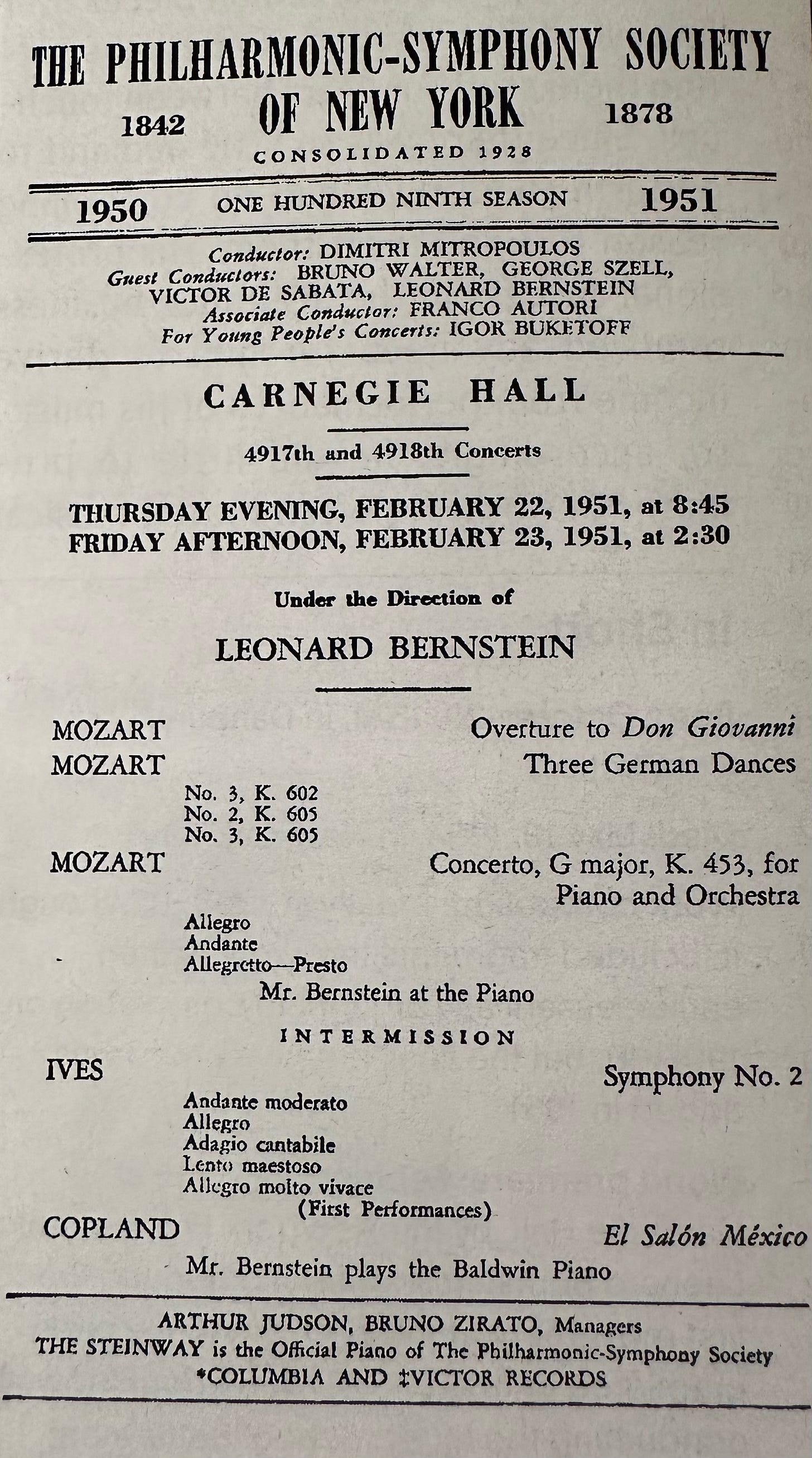

In February 1951, Ives was too nervous to attend Leonard Bernstein's premiere with this very orchestra, preferring to listen on the radio. Of that performance, the New York Herald Tribune critic Virgil Thomson wrote that the Second Symphony "speaks of American life with love and humor and faith. It is unquestionably an authentic work of art, both as structure and as communication."

After one of the toughest weeks in America in recent memory, the performance was catharsis. I can only imagine that Lenny would've been proud.

Dudamel conducted the orchestra with lyrical power. He danced as if attending the Fourth of July picnic evoked by the music. He summoned greater emotion from his first chairs by getting deeply in their faces and demanding more.

The Brahmsian sections were gorgeous—lush sound, beautiful flow. The American tunes that emerge throughout—"Columbia, Gem of the Ocean," "America the Beautiful," "Camptown Races"—were handled with grace if not quite abandon. That's the thing about Ives—he makes you hear your own country differently.

His reflections on the music of the Civil War and the Reconstruction era evokes a sonic landscape of people ultimately finding a way of harmonizing.

The Orchestra as Point of Light

These are dark times. But the American experience is so much more than violence and polarization and anger. It is also a young composer having her work played alongside the great modernists of American music. It is Bela Bartok fleeing oppression and pouring his heart into one last expression of life, brought alive by a 21 year-old from Korea.

And when Dudamel stepped into the violin section during the Ives, when he locked eyes with principal cellist Carter Brey, when he drew out that extra bit of brass in the finale—he fully involved the audience in that conversation about American history — and glory.

This is what live performance offers that recordings can't. The specific energy of this room on this night with these people.

The intensity is not that different from Citi Field after Juan Soto hits a home run, or the crowd sings My Girl when Francisco Lindor1 steps to the plate.

Real human connection between performer, audience and ability transcends into something greater.

New York City is special because all of this is available — if you choose to seek it.

Seek out the NY Philharmonic when Gustavo Dudamel is in town. Guaranteed home run.

Gustavo Dudamel returns to the NY Philharmonic throughout the season before officially taking over as Music & Artistic Director in 2026. Student rush tickets are available for most performances.

Doug Hesney is founder and president of the Cognitive Film Society. This is the first piece in "Cognitive Frames: In the Room," our new section covering live performance from the perspective of ticket-buying audiences.

The Mets are also classical pilled - with Katya Lindor playing the National Anthem on her violin the very same night