Editor's Note: This is Geoff Wolinetz’s third contribution to Cognitive Frames, following his pieces on Defending Your Life and L.A. Story. This time, he pairs two seemingly incompatible documentaries—the Maysles brothers' 1975 Grey Gardens (about Jackie Kennedy's reclusive relatives in their decaying Hamptons mansion) and Dean Fleischer Camp's 2021 Marcel the Shell with Shoes On (about a one-inch tall shell navigating an empty house).

It's an unexpected comparison that reveals something profound about solitude versus loneliness, and how we perform ourselves even—or especially—when we think we're alone.

After exploring how we perform for cities and audiences, Geoff now examines the most intimate performance of all: the stories we tell ourselves when no one's watching. Or when we pretend no one's watching. – D.H.

I'm a pretty social guy. I love being around people. I love talking to people and finding out who they are and what they're about. I love talking to servers in restaurants and the people checking out my groceries in Trader Joe's1. I love finding common ground with people. For me, it's one of the best things about being alive.

But I also love my alone time - to read, to write, to work, to solve a problem, to think or to just lounge and do nothing. And there are people out there who love doing that the way that I love being around people.

I don't say any of that with an ounce of judgment. But there's a nervous reality here, which is that solitude sits uneasily in our culture. We're conditioned to see it as loneliness, eccentricity, or loss, rather than as a space for creativity, resilience, and self-definition. Or, even more simply, a choice. Film is one way to peer into that choice from a lot of different angles: sometimes tragic, sometimes whimsical, sometimes deeply humane.

From the decaying East Hampton mansion of Grey Gardens (1975)2 to the tiny domestic world of Marcel the Shell with Shoes On (2021), these two films invite us to sit with characters who create meaning in solitude.

They're wildly different in tone and form, but they both ask the same question: what does it mean to live with yourself?

Solitude vs. Loneliness

In our culture, being alone is often seen through two opposing lenses: as a sign of failure or as a badge of self-sufficiency. The stigma of loneliness sits on one side and suggests that aloneness must mean social rejection or personal shortcoming.

The other side is this romanticized ideal of fierce independence: the quirky genius, the stoic wanderer, the person who just doesn't need anyone else to feel whole.3 As always, what sits between these poles is a far more nuanced truth: being by yourself is not just a condition to power through or celebrate, but something to be practiced. And art, with its ability to capture the inner workings of its subjects while at the same time inviting us to witness them, offers a compelling lens for exploring the tension between solitude and society.

So when I think about solitude vs loneliness on the screen, I think of Grey Gardens and Marcel the Shell with Shoes On. They're very different films, but I can't help but connect them in my head because they both feature lead characters who've been thrust into solitude.

And because they're on the screen being filmed, they help us see solitude not just as a state but as an act. One presents a decaying, performative, theatrical version of life on the margins; the other offers a whimsical, almost childlike portrait of a tiny being navigating an enormous world. And when you take the two together, they ask us to reconsider what it actually means to be alone, and whether solitude might be less about absence and more about one's ability to author their own path.

Grey Gardens: Solitude as Performance and Survival

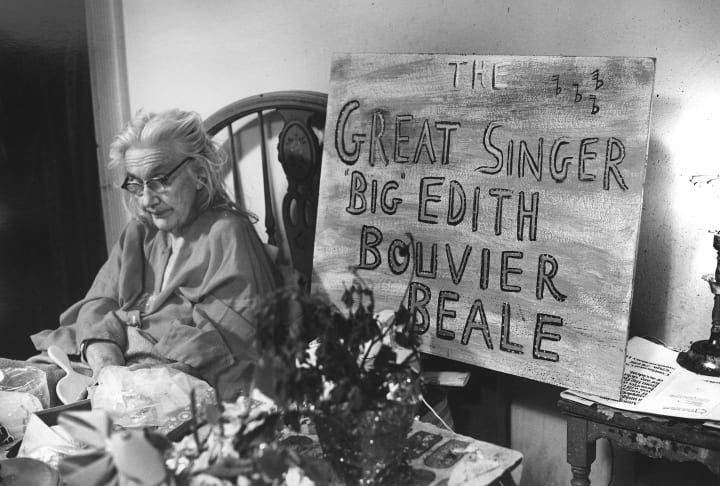

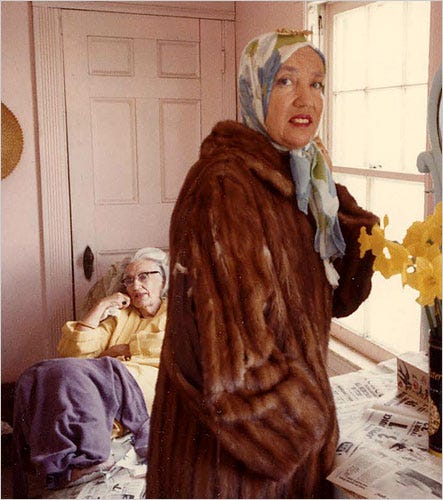

Albert and David Maysles' Grey Gardens immerses us in the bizarre, crumbling world of Edith Bouvier Beale ("Big Edie") and her daughter, Edith ("Little Edie"), relatives of former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. The Beales were once fixtures of Hamptons high society, but now live in near-total isolation in a decrepit, decaying mansion, sharing their home with raccoons, cats, and a tangle of memories of what once was. Little Edie, more than her mother, turns her isolation into a kind of bohemian performance art. Her outlandish costumes, monologues to the camera, and improvised dances have the movie vacillating between documentary and cabaret. Their solitude is both tragic and melodramatic.4

This is both prison and stage: the Beales may be cut off from the outside world, but they also seize the opportunity to construct their own narrative. Honestly, there's defiant resilience in this. As a viewer, it's easy to respect and admire their outright refusal to disappear quietly after they'd been cast out of their elite universe. But there is also a wild delusion here, as we wonder whether performance has overtaken reality for them.

Big Edie and Little Edie keep each other company, but it's easy to forget they're also trapped together. Their shared isolation is both their comfort and their curse. Grey Gardens is a reminder that solitude is never purely individual; it is always shaped by the people with whom we do (or do not) share our lives.

Marcel the Shell with Shoes On: Solitude as Whimsy and Wonder

If Grey Gardens is an exploration of eccentric isolation on the precipice, Marcel the Shell with Shoes On is its gentle, hopeful counterpoint. Marcel is a tiny shell with one googly eye and a pair of shoes, living in a house now mostly empty after its human occupants have gone. Unlike the Beales, Marcel does not seem embittered by his circumstances. Instead, he creates meaning from what remains, turning everyday domestic objects into tools, furniture, and playgrounds.5

The tone of Marcel reframes solitude as a space for wonder, not tragedy. The miniature scale of Marcel's world relative to the immensity of the outside world works as a metaphor for the richness of his inner life: small and detailed, but full of invention. And it's that curiosity that leads him beyond his solitude, as he seeks to reconnect with his lost family and build new forms of community. In Marcel's story, solitude is not the end state but the beginning, a space from which connection becomes more intentional and profound.

Between the Films: Echoes Across Tone and Form

What makes these two films so fascinating to compare is how they both blur the boundaries between documentary and performance. Grey Gardens is nonfiction, but the Beales' ostentatious self-presentation and delusions of grandeur only serve to complicate the idea of "truth." Marcel, though animated and fictional, is stylized as a mock-documentary, with its own earnest interviews and vérité-style. And one of the most remarkable things that links these two films is that they both suggest that solitude invites self-mythology. When we're alone, we can fashion and create whatever stories we want to explain our lives to ourselves (and to whoever might be watching).6

Space itself plays a critical role in shaping these myths. The Beales' mansion, overrun with decay, is both a symbol of lost glamour and also the physical manifestation of their isolation. By contrast, Marcel's home is bright and ordinary and a blank space for his ingenuity. But both films force the viewer to contend with their own position as furtive witness: are we intruding on private lives or invited into them? Do these portraits of solitude comfort or are they unsettling?

The Art of Solitude: Lessons Across the Spectrum

Grey Gardens and Marcel the Shell with Shoes On reveal that solitude can be more than just a condition. It can be the ultimate creative act. The Beales turn their exile into theater, while Marcel fashions meaning from his small corner of the world. The camera becomes a companion; a mirror that helps the subject see themselves.

It's that reframing that invites us to think of solitude not as a void but as fertile ground for shaping ourselves. When we opt to engage with our aloneness — whether to turn it into art, ritual, or story, we transform it into something worth witnessing (whether someone witnesses it or not).

And if that's true, then solitude is not simply the absence of others but the presence of ourselves. Grey Gardens and Marcel the Shell with Shoes On, one eccentric and tragic, the other tiny and tender, offer a wide spectrum of what it means to live within your own company. They remind us that the art of solitude lies not in withdrawing from life, but in writing it on our own terms. Whether in a decaying mansion or a cozy nook, solitude can become a stage, a workshop, even a sanctuary.

In the end, living with yourself is less about being apart from the world and more about choosing how to inhabit it.

Where to Watch

Grey Gardens (1975): Available for streaming on HBO Max, and for rent on Amazon Prime Video, Apple TV and other platforms.

Marcel the Shell with Shoes On (2021): Available for rent on Amazon Prime Video, Apple TV+, and other platforms

This comes with great embarrassment for my children, which might be my favorite part of being this way

The mansion itself very much has an "if these walls could talk" type vibe, given that the women lived there for over 50 years and then was purchased by Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee and his wife Sally Quinn, who lived there until Bradlee's death in 2014. It's currently owned by fashion designer Liz Lange

The Unabomber and the Japanese soldier who kept fighting World War II until the 1970s also fit in this category, but let's stay positive here

Grey Gardens is pretty unsettling in a lot of ways, but Little Edie's performances are the absolute visual definition of the word

I tried making a trampoline out of toothpicks and bread, but it didn't work

One of the funniest lines in the entire run of the show Scrubs was Sarah Chalke describing her ethos on life "I have a sign that says 'Dance like no one is watching,' which I do in my living room … with the shades drawn just in case someone is watching"

I really loved this piece. You articulated something I’ve been circling around in my own work — the way solitude provides the space for ideas to take root, and collaboration gives them shape. Thank you.