The Trouble with Windows

On voyeurism, the flaneur and Hitchcock’s masterpiece Rear Window

Editor's Note: Sometimes the perfect piece finds you at exactly the right moment. Buku Sarkar —whose fiction and photography have appeared in The New York Review of Books, n+1, and Threepenny Review—discovered Cognitive Frames just as she published this extraordinary essay on her Substack, My Dead Flowers.

Winner of the Andrew Nelson Lytle Prize, author of the monograph Photowali Didi, and co-writer of “The Shameless” (which premiered at Cannes' Un Certain Regard in 2024), she reached out asking if we "accept submissions or do collaborations."

The answer, emphatically, is yes.

We're incredibly proud to work with Sarkar and to republish—with her permission—this remarkable piece on Rear Window. It exemplifies everything we seek: criticism that weaves personal memory through theoretical insight without losing either thread. Writing from Paris, drawing on her childhood in Calcutta, she transforms Hitchcock's voyeuristic masterpiece into something startlingly new. Her book “Not Quite a Disaster After All” arrives in the US this Fall. - D.H.

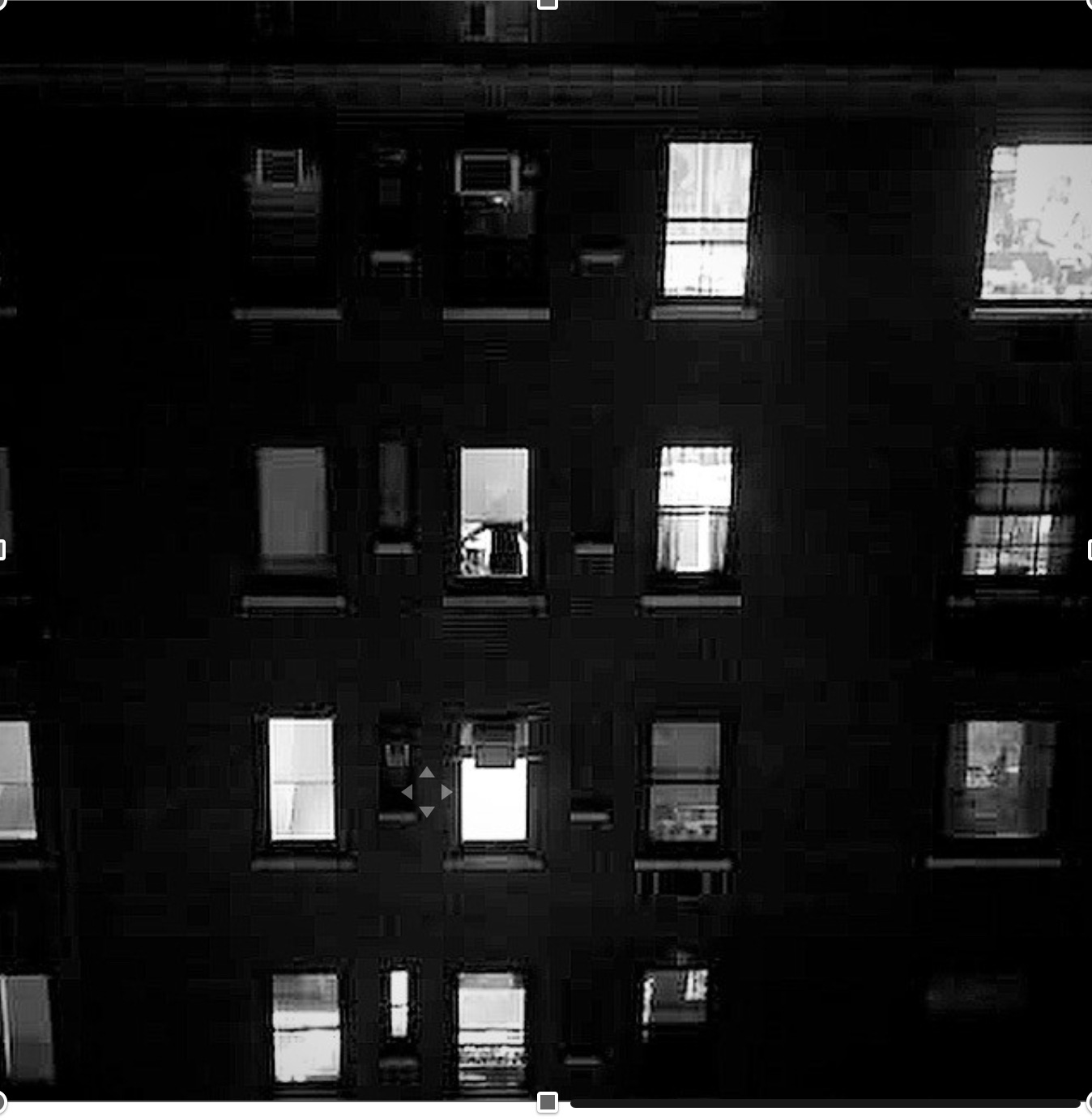

In the dim light of the courtyard, a figure lingers by the window, her gaze fixed on the world beyond. She is not merely observing; she is participating in a delicate dance of presence and absence. This act of watching, of being both seen and unseen, is the essence of the flâneur—a term that Edmund White explores in his work The Flâneur: A Stroll Through the Paradoxes of Paris. White describes the flâneur as someone who "merges with the crowd," an observer who is simultaneously detached and deeply engaged with the city around them. This duality allows the flâneur to witness the unnoticed, to find stories hidden from the visible world, , and to understand life outside (and ironically, inside), like a spy but with a degree of fascination.

One watches Rear window and then the film watches you back—a film that turns every viewer into a co-conspirator, a fellow voyeur peering through venetian blinds at the messy theater of human existence. We are all complicit in the film. Us the viewer watching James Stewart watch his neighbours through his windows. The window behind which he remains incapacitated but becomes a witness to a larger drama playing out on the other side.

What makes Rear Window so unnervingly brilliant isn’t just what we see, but how we see it. Hitchcock constructed the film entirely on a colossal composite set, “pre-lit every one of the 31 apartments for both day and night,” orchestrating a lighting symphony that resembled “the console of the biggest organ ever made.” Each ray of illumination becomes a character in its own right. The courtyard is alive, each apartment a window into loneliness, desire, despair, and resilience—a vertical village where privacy becomes performance and solitude turns spectacle.

Miss Torso dances in her skimpy leotard, shadow and sinew flitting against the backdrop of her lit window, resisting the advances of men in fleeting glimpses—hips, shoulders, and the occasional dismissive hand flick captured in high contrast black-and-white. Miss Lonelyhearts arranges a table for two in an almost ritualistic precision, raising her glass to an invisible companion, rehearsing conversations that will never occur. And the songwriter, a top-floor specter of melody, lets his piano provide the courtyard’s soundtrack, each note drifting through the open windows like whispered gossip. Thorwald’s apartment, by contrast, is a study in absence and menace. We see him leaving at odd hours, carrying packages that invite speculation; we watch him scrub his bathroom walls, each stroke of the sponge a potential confession. And yet, it is his darkened, cigar-lit silhouette that lodges in memory, the absence of illumination more revealing than any light.

Edmund White describes the flâneur as someone who “merges with the crowd,” an observer who is simultaneously detached and deeply engaged with the city around them. But Jeff cannot merge with anything. His broken leg has transformed him into a stationary observer, a reluctant prisoner of his own apartment. The mobility that defines White’s Parisian wanderer becomes, in Jeff’s case, an obsession, a desperate reaching through lenses and windows toward lives he cannot touch.

At eight, I adopted my own methods of observation. Our apartment in Calcutta faced another complex across a narrow courtyard, and every afternoon after school, I perched on our terrace after school. I followed movements: the old man on the ground floor hacking through invisible ailments; the twin toddlers pressing their foreheads to windowpanes; the third-floor lady with her white fluffy dog, combing its fur with the devotion . Inside, I arranged my Grace Kelly paper dolls—pistachio suits, flowing negligees, pencil skirts and silk blouses—across the floor. Each posed in scenarios mirroring the courtyard’s dramas. I knew everything that happened in that building across from our house: who fought, who whispered, who paused. And I was secretly so proud that I managed to do so within months of watching Rear Windows for the first time completely undetected.

Yet one day, the third-floor lady looked up, caught my gaze, and called out: “Would you like to come play with him?” My secret surveillance dissolved into exposure. I was not the observer but the observed, and the lesson was exquisite and mortifying. This moment of recognition—the sudden reversal from watcher to watched—captures the essential anxiety at the heart of both flaneurism and voyeurism. Teju Cole’s Julius in Open Cities experiences similar moments of uncomfortable visibility, when his carefully maintained anonymity crumbles and he finds himself seen, catalogued, perhaps even judged by those he has been observing.

The window is never merely a frame. In Rear Window, it becomes a lens, a threshold between self and other, public and private, freedom and confinement. Each apartment is a discrete channel, each gesture a story. Windows frame, they isolate, they reveal— a different world, each frame a different story; they construct a panopticon in which every observer is also observed. François Truffaut wrote, “The courtyard is the world, the reporter/photographer is the filmmaker, the binoculars stand for the camera and its lenses.” In this space, to watch is to participate, to be complicit, to wrestle with desire, empathy, and dread simultaneously.

Both White’s and Cole’s flaneurs explore urban watching. White acknowledges the flâneur’s potentially predatory gaze, the way that aesthetic distance can become emotional callousness. Cole pushes this further, examining how the act of looking is inevitably shaped by power, race, class, and history. Julius’s wanderings through New York are not innocent—they are informed by his position as a Black intellectual navigating predominantly white spaces, his observations colored by an awareness of how he himself is being observed and categorized.

But in Rear Window, voyeurism is more simple—a deep desire to know the ‘other’. Hitchcock is not moralizing on the idea of ‘watching’. He is meditating on the act itself. This obsession of the ‘other’, outside, while being home bound and trapped inside, is the very marrow of Rear Window. The Kuleshov effect merges us with Jeff’s gaze: Miss Lonelyhearts raises her glass, Thorwald moves in shadow, Lisa’s sleeve catches a sliver of light—and we are implicated in every moment. The ethics of voyeurism unfold in layers, mirrored by obsession: Stewart’s relentless curiosity, Thorwald’s secretive compulsions, Miss Lonelyhearts’ yearning—all trapped, all observing, all being observed. Freedom becomes perspective; confinement, clarity.

Consider Miss Lonelyhearts at dinner. At precisely 7:01, she sets her table: a single plate, a knife to the left, fork to the right, glasses aligned with obsessive care. At 7:03, she seats herself, adjusts the napkin, begins to pour wine. At 7:05, she raises her empty glass to an imagined companion. At 7:06, she inhales deeply, closes her eyes, whispers a toast. The candlelight flickers across her face, a mirror of isolation that is nonetheless alive, deliberate, performative. This repetition is punctuated by the distant piano of the songwriter, every note a reminder of the external world intruding upon her solitude.

Here is flaneurism turned inward, the urban walker become urban dweller, still moving through ritual and routine but contained within the four walls of a single room. Miss Lonelyhearts embodies what might be called the domestic flâneur, creating her own geography of observation within the limited landscape of her apartment. Her nightly dinner performance transforms solitude into spectacle, privacy into a kind of public art. She is simultaneously the observer of her own life and the observed subject of Jeff’s—and our—fascination.

Jeff’s gaze is never neutral. It is implicated, ethical, invasive, compassionate, and obsessive. His interest in Thorwald, in Miss Lonelyhearts, in Lisa, mirrors our obsessions with the ‘other’. The film interrogates whether observing is inherently exploitative or necessarily human. We watch to understand, to control, to empathize, to survive. But in doing so, we expose ourselves to the same scrutiny. Confinement is relative: Stewart’s body is trapped; Thorwald’s actions are constrained; Lisa navigates social expectation; Miss Lonelyhearts is a voluntary prisoner of ritual. Who, in this courtyard, is free, and who is not?

This question echoes through Cole’s Open City, where Julius’s apparent freedom to wander masks deeper forms of constraint—psychological, historical, cultural. His walks through Manhattan become a form of working through trauma, a way of processing not just personal history but collective memory. The city becomes both text and context, a palimpsest where past and present overlap, where observation becomes a form of archaeology. Similarly, White’s flâneur is both liberated and limited by his role as professional observer, free to move but bound by the very detachment that enables his mobility.

And of course, no writing of Rear Window is complete without a dedication to Grace Kelley and her outfits.

The first time Lisa Fremont appears on screen, she is luminous, a close-up so incandescent it seems to cast its own shadow. Grace Kelly enters in “a gorgeous silk negligee” that “looks fancy enough to be an evening gown,” yet the black-and-white dress with its “deep V neckline at the front and back, and full, frothy skirt” steals your breath entirely. It is elegance rendered motionless, a silent promise of transformation. This is the perfect Grace Kelly balance between sexy and chic, the 1950s distilled into a single frame of fabric and bone structure, and it signals immediately that this woman is both spectacle and observer.

Edith Head, the legendary designer behind these garments, orchestrates a narrative through cloth. That first evening dress—a fitted black bodice with off-the-shoulder, deep V cut neckline, cap sleeves, and mid-calf layered chiffon tulle skirt—unfurls like a choreography of light as she illuminates each lamp in Jeff’s apartment. Every thread whispers sophistication, every fold marks a boundary between her world and his, a Parisian elegance landing in Manhattan’s gritty courtyard. She describes it as “straight off the Paris plane”—and the camera, in its intimacy, believes her. Later, in a pistachio-colored suit over a white halter top, paired with a pillbox hat and short veil, Lisa becomes an exercise in transformation. A single removal of the jacket and hat alters her entirely—society lady dissolves into approachable, into intimate. Each gesture, each piece of fabric, marks a transition: from observer to participant, from distance to proximity.

This says something deeper than mere fashion. Like Teju Cole’s Julius wandering through New York in *Open City*, Kelly’s Lisa exists in a liminal space between watching and being watched. Cole’s protagonist moves through the city with the measured gait of the contemporary flâneur, absorbing fragments of overheard conversations, glimpsed interiors, the accidental intimacies that urban life affords. But where Julius remains largely invisible, a ghost drifting through Manhattan’s arteries, Lisa’s visibility is her power. Her costumes announce her presence even as they protect her secrets, each outfit a carefully constructed persona that allows her to navigate between worlds.

The black silk organza dress with translucent cap sleeves emerges “darkly, at the pivotal point in the film, when Lisa starts to believe Jeff, and that the man they are watching is a murderer.” Costume is character. Fabric is foreshadowing. And it acts as a way to seduce a man who is not just wheelchair bound but seems more interested in his neighbours than her attention, which she throws at him. Even the overnight bag, with its silk negligee that “honestly looks fancy enough to be an evening gown,” becomes a silent actor in the story, hinting at the dangers and intimacies to come. When Lisa climbs into Thorwald’s apartment, her wardrobe functions as armor and signal. The soft shimmer of her silk blouse catches the faint light of the room, revealing apprehension, curiosity, daring—all without dialogue. Her pencil skirt clings just so, suggesting elegance maintained under duress. Each shoe click against the hardwood floor is amplified in the stillness of the apartment, a Morse code of grace, poise, and silent rebellion.

The genius of *Rear Window* lies not in its resolution of these tensions but in its insistence on their perpetual presence. The film ends not with clarity but with a return to watching—Jeff, both legs now in casts, asleep while Lisa reads, the courtyard continuing its endless cycle of revelation and concealment. The surveillance has not ended; it has simply been redistributed. Lisa now holds the binoculars, her gaze directed not at the neighbors but at Harper’s Bazaar, a different kind of window into lives she might inhabit.

Rear Window reminds us, that behind every window, behind every drawn curtain, behind the blinds where we hide, is a parallel life, inaccessible yet so deliciously imaginable and witnessed—What would we do without these windows? Behind each a different story, all the lives we will never know.