The Films of J.D. Salinger

America's Most Famous Literary Recluse Spawned Legions of Spiritual Adaptations

If there’s one thing I hate, it’s the movies. Don’t even mention them to me. - Holden Caulfield - The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

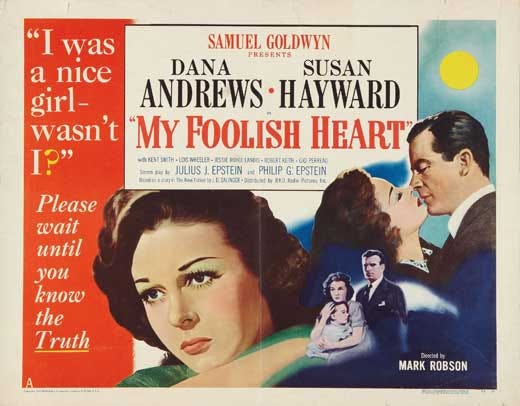

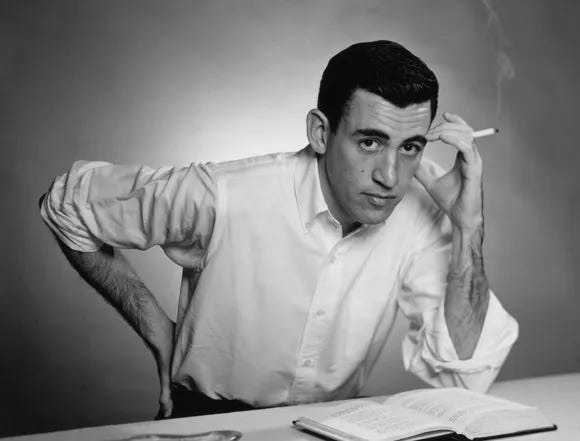

After “Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut” became the weepy 1949 Hollywood melodrama My Foolish Heart (an event he considered a massive betrayal) J.D. Salinger never allowed another film adaptation. Hollywood never stopped calling for The Catcher in the Rye. He never stopped refusing.

And yet Salinger’s fingerprints appear everywhere in American cinema—and beyond. His Glass family haunts Wes Anderson’s entire filmography. Wounded romantics influenced by his characters appear in films from Metropolitan to Magnolia. His alienated young men—Holden Caulfield’s spiritual descendants—populate the French New Wave and American auterist cinema from the 1970s to today.

The man who hated movies became one of Hollywood’s most influential and uncredited screenwriters. The paradox tells us something essential about both Salinger and the art form he rejected.

Salinger once occupied the highest pedestal of American literature. Today he's rarely discussed with the reverence I encountered in high school.

But I was inspired to revisit his work over the Christmas break. What did I find? With alienated young men decrying “phony” institutions, with romantic longing reasserting itself against algorithmic optimization, with a New Romantic counterculture emerging across cinema and music—Salinger demands reexamination.

His core questions—What do we owe our gifts? What do we owe each other? How do we maintain wonder in a world that only cares for optimization and materialism? — Are the questions of our time.

The Last Romantics

The best thing, though, in that museum was that everything always stayed right where it was. Nobody’d move. You could go there a hundred thousand times, and that Eskimo would still be just finished catching those two fish, the birds would still be on their way south, the deers would still be drinking out of that water hole, with their pretty antlers and their pretty, skinny legs…

Nobody’d be different. The only thing that would be different would be you. Not that you’d be so much older or anything. It wouldn’t be that, exactly. You’d just be different, that’s all.

- The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

I was introduced to Salinger in high school as the godfather of cynicism. Holden Caulfield is still shorthand for every disaffected youth calling out adult hypocrisy. “Phony” entered the American vernacular as accusation, dismissal, teenage sneer.

But this misreads Holden entirely.

Holden and the Glass family aren’t rejecting the world because they’re too cool for it. They’re mourning it because they loved it too much and find it consistently unworthy and unfair. Re-reading Holden Caulfield at nearly (*gasp*) 50, I just want to put my arm around the kid and give him a sandwich.

The death of Holden’s beloved brother Allie has given him deep and early insight into the fundamental absurdity of modern life. He knows that the striving is meaningless. And yet he is told he must strive. Like his antecedent in Goethe’s proto-romantic novel The Sorrows of Young Werther, Holden seeks the sublime and is confronted only with the ordinary and the vulgar—both in society and within himself.

That’s Romanticism with a capital R—the same impulse that drove Keats and Shelley, the Brontës and Beethoven. The belief that feeling deeply is both humanity’s highest capacity and its greatest vulnerability.

Salinger was part of this history directly. He landed on Utah Beach on D-Day, carried manuscript pages of The Catcher in the Rye through the European campaign, and was among the soldiers who liberated Kaufering IV, a Dachau subcamp. After checking himself into a psychiatric hospital in Nuremberg, he came home to an America that wanted to forget everything and move forward fast.

The post-war boom offered luxuries and opportunities unimaginable to previous generations. Levittown. Television. Old neighborhoods and identities to transcend. Who had time for deeper questions when there were markets to conquer?

Salinger’s work was a fly in that ointment. His characters—Holden Caulfield, the Glass family—were among the earliest to reckon with the alienation of a world centered on materialism and rapacious growth. These were the Romantic refugees. Stranded in an age that had no use for wonder.

And from Salinger’s refugees, the movies made icons.

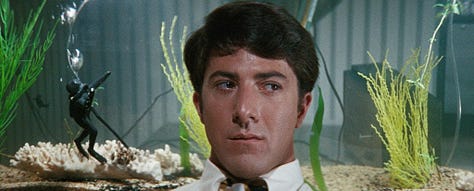

Marlon Brando’s sneer in The Wild One. James Dean’s wounded confusion in Rebel Without a Cause. Dustin Hoffman’s Benjamin Braddock floating in a swimming pool. These weren’t just performances—they were Holden Caulfield given a body, a motorcycle, a cigarette. Beyond Hollywood, the French New Wave directors who revolutionized cinema in the late 1950s understood what Salinger was doing: not celebrating disaffection but anatomizing the pain of romantics born into an unromantic age.

The loose-limbed alienation of Belmondo and Seberg walking the Champs-Élysées in Breathless. Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel, frozen in that final frame of The 400 Blows, has nowhere to go—the same nowhere Holden faces when he asks where the ducks go in winter.

The archetype remains inexhaustible.

Seymour Supreme

Sybil said, "What happens to them?"

"What happens to who?"

"The bananafish."

"Oh, you mean after they eat so many bananas they can't get out of the banana hole?"

"Yes," said Sybil.

"Well, I hate to tell you, Sybil. They die."

"Why?" asked Sybil.

"Well, they get banana fever. It's a terrible disease."

- A Perfect Day for Bananafish, by J.D. Salinger

Despite all the promise in the world, 31-year-old Seymour Glass puts a bullet in his head.

“A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” the opening story in Nine Stories, begins with Seymour’s wife Muriel on the phone with her mother, discussing whether Seymour is safe to be around. It ends with Seymour looking at sleeping Muriel and firing a bullet through his right temple.

In all subsequent Glass family stories, we never meet him alive again. He lives only in memory, and his suicide is the catalyzing event for everything written about the Glass family afterwards. Franny Glass’s spiritual breakdown, Zooey Glass’s rage at a world that destroyed his brother, Buddy Glass’s obsessive chronicling of his family’s—but really his brother’s—history. All of it is aftermath.

Seymour was the eldest, the wisest, the most spiritually attuned of the Glass children. A poet. A professor. A veteran who came home from the war and found he couldn’t breathe in the world that was waiting. We meet Seymour again in the memories of his siblings—and find that he was always an unusual empath. Someone who just knew what the people around him were thinking and feeling.

Seymour (and perhaps Salinger) surely suffered from PTSD, but his crisis—as laid out in Raise High the Roof Beam Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction—was deeply spiritual. Seymour lacks the ability to reconcile all he has seen and will see. He is alienated from the mundane, despite a desperate desire to connect with it.

There is no sublime, there is no mundane, and for Seymour there is nothing.

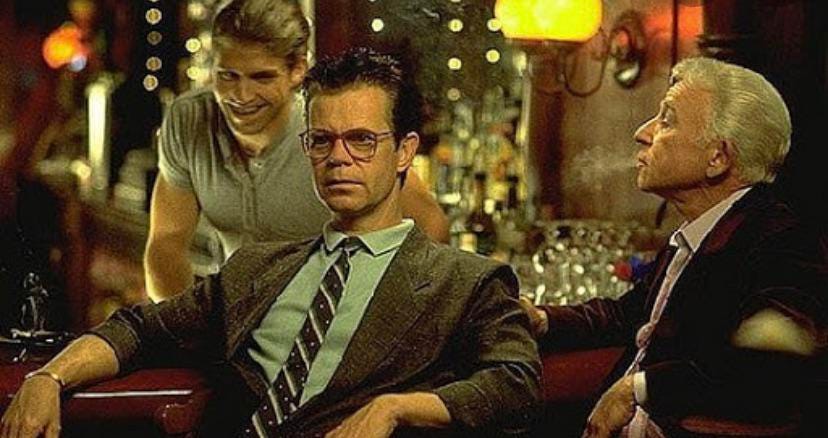

Seventy-five years later, Josh Safdie gave us his mirror image.

Marty Mauser—brought to life in Timothée Chalamet’s electric performance in Safdie’s 2025 masterpiece Marty Supreme—is Seymour Glass’s doppelganger. Both are Jewish geniuses confronting the impossible promise of post-war America. Both are surrounded by people who cannot fathom the depth of their alienation. Both are traumatized by the gap between romantic ideals, modern materialism, and familial responsibilities.

Seymour retreats into silence and spiritual practice and eventual self-annihilation. Marty hustles. He plays every angle. He finds every edge, schemes his way through a world of fixers and marks and front men. “Hitler’s greatest nightmare,” he calls himself—a Jewish kid from nowhere who’ll secure his own particular piece of the American dream.

Safdie—himself a Jewish filmmaker working seventy-five years after Kaufering IV, in an America where Jewish success is no longer exceptional but expected—can imagine redemption because he inherits a different relationship to catastrophe. Seymour carried the camps in his body. Marty carries them in cultural memory, which is painful but survivable.

Both Seymour and Marty fail in their pursuit of happiness.

But Safdie offers his character something that Salinger couldn’t allow: a way through.

Marty Supreme allows redemption through human connection. The film lets you root for Marty’s hustle, lets you believe that talent and will can conquer the machinery of the world. Then it shows you the cost. Trophies can’t keep you warm. The system will grind you down regardless of your skill.

But Marty doesn’t die alone in a Japanese hotel room. He learns—barely, painfully—that the people who loved him before he was somebody will still be there after the world forgets his name. The dream is a myth is real is a dream—but in the end, all you have are the people who love you.

This is the evolution of the Salinger question across seventy-five years of American film. What happens to romantics in an unromantic age?

One answer appears in Marty Supreme itself—not in Chalamet’s performance but in the woman who orbits his rise and fall. Gwyneth Paltrow plays Kay Stone, a faded movie star. Her glamour calcified into something brittle. It’s a supporting role, but it rhymes with her most iconic one: another damaged woman surrounded by men who study her rather than see her.

A Glass Family Reunion

You’ve got a goddamn bug today—you know that? What the hell’s the matter with you anyway?"

Franny quickly tipped her cigarette ash, then brought the ashtray an inch closer to her side of the table. "I’m sorry. I’m awful," she said. "I’ve just felt so destructive all week. It’s awful. I’m horrible."

"Your letter didn’t sound so goddamn destructive."

Franny nodded solemnly. She was looking at a little warm blotch of sunshine, about the size of a poker chip, on the tablecloth. "I had to strain to write it," she said.

- Franny and Zooey, by J.D. Salinger

Margot Tenenbaum—the adopted sister, the secret smoker, the playwright who “hadn’t written a word in years”—is Franny Glass in eyeliner and a fur coat. Wes Anderson barely hid his debt.

In a 2000 interview with Tod Lippy, conducted while writing the Tenenbaums screenplay, Anderson addressed the Glass family comparison directly: “The Glasses always seemed so sad. Sad and superior. And Buddhist. We don’t have that.”

That last distinction matters. Anderson’s revision of Salinger is theological—his Glasses survive. More than that: they reunite.

What Anderson understood—what makes Margot more than pastiche—is the specific wound Franny carries. In Salinger’s novella, Franny collapses in a restaurant clutching a small green book, repeating the Jesus Prayer while her boyfriend Lane drones about his academic paper. She can’t take it anymore. Not Lane specifically, but what Lane represents: a world of credential-seeking phonies who’ve mistaken cleverness for wisdom, who perform intelligence rather than feel anything.

Margot doesn’t collapse. She dissociates. She takes baths that last hours. She smokes in secret on the service elevator. She stares at nothing while her husband Raleigh—a neurologist who literally studies her—explains what he thinks she’s feeling.

Same wound, different armor. Both women surrounded by men who study them rather than see them.

Beyond Margot, the Glass family and the Tenenbaums are essentially the same family, separated by fifty years and a few tax brackets. Both are clans of child prodigies in upper Manhattan. Both produced early achievers—the Glass children on It’s a Wise Child, the Tenenbaum children with tennis championships and produced plays and business empires built on Dalmatian mice.

“Freaks,” Zooey calls himself and Franny. Seymour and Buddy raised them on the great religious texts, on poetry, on standards the modern world had abandoned. They were prepared for a world that no longer existed—if it ever had.

The Tenenbaum children face the same betrayal, secularized. Their early promise calcified into expectation, then disappointment, then dysfunction. Richie’s tennis career collapsed. Margot’s playwriting dried up. Chas’s business acumen curdled into paranoid overprotection. “Genius” becomes a prison for both families.

Even the homes rhyme. The Glass apartment in Franny and Zooey is practically a character—books stacked everywhere, the bathtub where Zooey reads while Franny has her breakdown in the next room, every surface holding something someone was reading or thinking about. It’s not decoration. It’s sedimentation. The accumulated intellectual life of a family that lived in ideas.

The Tenenbaum house operates the same way. The zebra wallpaper. Richie’s hawk, Mordecai. The board games and fencing equipment. Objects accrete like coral, marking obsessions and phases and abandonments. Both homes are monuments to interiority—museums of who these families used to be.

But Salinger never lets his family gather. We meet the Glass siblings separately, in isolated stories, always in the aftermath of Seymour’s death. Buddy writes about Seymour. Zooey argues with Franny through a bathroom door. The parents hover at the edges. There is no reunion, no reckoning, no scene where everyone sits in the same room and confronts what they’ve lost and who they’ve become.

Anderson gives the Tenenbaums exactly that. Royal’s false illness brings the scattered children home. The family that had splintered into private dysfunction reassembles under one roof—awkwardly, painfully, but together. They eat meals. They have it out. Chas finally screams at his father. Margot’s secrets surface. The estranged become the reconciled.

“I’ve had a rough year, Dad,” Chas admits through tears, finally letting Royal see him.

It’s the Glass family reunion Salinger never allowed

Salinger Inspired Cinema

“I don't really deeply feel that anyone needs an airtight reason for quoting from the works of the writers he loves, but it's always nice, I'll grant you, if he has one.” - Buddy Glass

- Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters & Seymour: An Introduction, by J.D. Salinger

Salinger’s specific works map onto specific films with uncanny precision—not as vague influence but as structural blueprints, character templates, stolen gestures that reveal how deeply his innovations shaped American and international cinema.

“Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut” → Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (Ryusuke Hamaguchi, 2021)

Salinger’s 1948 story and the third segment of Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s triptych share a near-identical architecture: two women who shouldn’t be together find themselves in enclosed space, use the encounter to excavate grief over lost loves, and emerge transformed by confessions neither expected to make. It proves a far superior adaptation of “Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut” than My Foolish Heart.

Eloise Wengler and her former college roommate Mary Jane spend a snowy Connecticut afternoon drinking highballs. What begins as gossip about old classmates gradually unearths Eloise’s profound grief over Walt Glass—her great love, killed absurdly in the war when a Japanese stove exploded while being packed. The story’s title references Walt’s tender nickname for Eloise’s twisted ankle: “Poor Uncle Wiggily.” By story’s end, drunk and devastated, Eloise holds her daughter Ramona’s glasses to her cheek and sobs while asking Mary Jane the story’s gutting final question: “I was a nice girl, wasn’t I?”

Hamaguchi’s “Once Again” inverts and deepens this structure. Set in a near-future where a computer virus has forced the world offline, the segment follows Natsuko, an IT engineer who attends her twenty-year high school reunion hoping to reconnect with her first love—a woman named Mika who never appears. The next day at the train station, Natsuko spots a woman on the escalator she believes to be the person she’s been seeking. The woman recognizes her too and invites her home.

They spend the afternoon catching up, reminiscing about the past. Then the devastating reveal: when Natsuko begins to let heavy feelings off her chest, the other woman admits she’s forgotten Natsuko’s name. They realize they’ve mistaken each other for former classmates—they didn’t even attend the same school. A case of double mistaken identity.

But instead of parting in embarrassment, they continue. Natsuko reveals the person she mistook this stranger for was her first love, that they broke up in college, that she’s carried the loss for twenty years. The two women begin to role-play as the people they thought each other was—essentially performing therapy for one another, allowing both to achieve closure on relationships left unresolved for decades.

The parallels operate at multiple levels. Both stories trap women in domestic space—Eloise’s Connecticut living room, the stranger’s Japanese home—where alcohol or circumstance loosens inhibition. Both use the afternoon encounter to process romantic grief that has calcified into permanent dissatisfaction. Both feature women confronting who they used to be: Eloise asking if she was once “a nice girl,” Natsuko literally acting out the reunion she never got to have.

The crucial difference is resolution. Salinger’s ending is devastating—Eloise drunk, sobbing, holding her daughter’s glasses, the afternoon having excavated pain without providing release. Hamaguchi allows his strangers to become genuine friends through their shared confession. The mistaken identity that should have been humiliating becomes liberating. Both works understand that women carry romantic grief for decades, sedimented into permanent dissatisfaction. Salinger offers only the wound. Hamaguchi, characteristically, offers the beginning of healing.

Hamaguchi shows what a faithful adaptation might have looked like: intimate, devastating, trusting the audience to read between lines—but with the grace to imagine what happens when strangers give each other permission to grieve.

The Glass Family → Magnolia (Paul Thomas Anderson, 1999)

The Glass family saga and Paul Thomas Anderson’s sprawling Los Angeles ensemble piece ask the same haunting question: what happens to gifted children when the spotlight fades? Both answer with portraits of damaged adults, suicidal impulses, and the psychological burden of early genius—delivered through interconnected narrative structures that reveal thematic unity across disparate storylines.

Seymour exemplifies the destroyed prodigy archetype. He entered Columbia at fifteen, became a professor at twenty, and committed suicide in 1948—shooting himself in a Florida hotel room while his wife sleeps. Franny experiences a nervous breakdown in her twenties, disgusted by “phoniness” and paralyzed by hyper-analysis of her own spiritual seeking. Zooey, a successful television actor, states the Glass children have become “freaks” because “their brothers taught them too much too young.”

Magnolia weaves nine major storylines together over one San Fernando Valley day, connected through a quiz show called “What Do Kids Know?” Quiz Kid Donnie Smith—played by William H. Macy—is what happens to a Glass child without the spiritual vocabulary. A former champion of the show decades earlier, exploited by parents who took all his prize money and left him penniless, possibly brain-damaged from a lightning strike, he works dead-end jobs and delivers the prodigy’s epitaph: “I used to be smart, but now I’m just stupid.”

Stanley Spector, the brilliant current contestant, functions as the “before” photograph—what Donnie once was, what the Glass children were before the radio show ended and real life began. Stanley is exploited by his father, who wants only the money Stanley makes, regardless of the emotional toll. Studio staff prevent Stanley from using the bathroom; he wets himself on-air. The two characters exist as mirrors, reflecting the beginning and end of the child prodigy’s arc.

Both works reach for transcendence as escape from exploitation. Franny’s Jesus Prayer obsession and Seymour’s Zen Buddhism find their equivalent in the film’s rain of frogs and the extraordinary “Wise Up” sequence where characters simultaneously sing about facing truth. Both indict the systems that commodify children’s intelligence for entertainment value. Both suggest gifted children often become adults too sensitive for the world that celebrated them.

“The Laughing Man” → Moonrise Kingdom (Wes Anderson, 2012)

These two works share perhaps the most structurally precise parallels—both depicting organized groups of boys whose carefully constructed fantasy worlds are disrupted when adult romantic chaos intrudes.

Salinger’s 1949 story uses a triple-layered frame: an adult narrator recalls being nine in 1928, belonging to the Comanche Club—an after-school organization run by “the Chief,” a 22-year-old law student whose greatest gift is the serialized adventure he tells: the Laughing Man, a disfigured hero who wears a mask of poppy petals and outwits his nemesis.

The Chief’s story parallels his life. When beautiful Wellesley student Mary Hudson becomes his girlfriend and joins the outings, the Laughing Man’s fortunes improve. When the romance fails—Mary runs away after a heated, inaudible conversation, surrounded by subtle hints of pregnancy—the devastated Chief abruptly kills off his hero. The Laughing Man rips off his poppy-petal mask and dies. As the narrator exits the bus, “the first thing I chanced to see was a piece of red tissue paper flapping in the wind against the base of a lamppost. It looked like someone’s poppy-petal mask.” Fantasy becomes litter. Innocence is destroyed by something the children cannot comprehend.

Anderson’s film follows the Khaki Scouts of North America, Troop 55, on a fictional New England island in 1965—led by Scout Master Randy Ward, an earnest math teacher who considers scouting his true calling. But Anderson inverts the structure: here the children’s romance is central. Twelve-year-old orphan Sam Shakusky and troubled Suzy Bishop run away together into the wilderness, both escaping adult dysfunction. Suzy’s parents are lawyers whose marriage is crumbling; her mother conducts an affair with the local police chief that Suzy discovers through binoculars.

Both works position boys’ organizations as self-contained worlds governed by their own rules—spaces where children find identity apart from family dysfunction. Both feature adult leaders who bridge childhood and adulthood, providing meaning through ritual and story.

The crucial difference lies in the ending. Salinger’s is tragic: the poppy-petal mask becomes trash, the boys are devastated by adult heartbreak they can’t understand. Anderson allows fantasy to survive in transformed form. A hurricane destroys the cove where Sam and Suzy made their camp, erasing it from the official map. But Sam paints it from memory. The cove is immortalized in art even as it’s erased from geography. Both works acknowledge childhood fantasy cannot survive unchanged—but Anderson offers redemption where Salinger offers only loss.

Down with Phonies

Keep me up till five because all your stars are out, and for no other reason…Oh dare to do it Buddy! Trust your heart. You’re a deserving craftsman. It would never betray you. Good night. I’m feeling very much over-excited now, and a little dramatic, but I think I’d give almost anything on earth to see you writing a something, an anything, a poem, a tree, that was really and truly after your own heart. - Seymour Glass, as told by Buddy Glass

- Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters & Seymour: An Introduction, by J.D. Salinger

Salinger would have hated every one of these films — particularly as spiritual adaptations.

Despite their complexity and humanity, they offer what he refused to provide: resolution. Anderson lets Richie live. Safdie lets Marty find his people. Hamaguchi lets strangers become friends. These are beautiful evasions, Hollywood’s irrepressible need to heal.

Holden knew better. He spends much of Catcher complaining how movies betray life, and flatten sentiment into something consumable for phonies. The happy ending isn’t just aesthetically false—it’s a lie about how the world works.

Now the optimized age has produced its own Holdens—young romantics who can see the algorithm behind every recommendation, the data harvest behind every interaction, the engagement metric behind every ending. The resolutions that once felt earned now feel engineered. The system is showing its seams.

This is why New Romantic Cinema is a growing movement. Films like One Battle After Another, Sinners, Blue Moon, Weapons, and even Superman resurrect Salinger’s melancholy defeats, by insisting on feeling in an age that has made feeling inefficient.

Sometimes it’s messy, but it isn’t phony.

Incredible write-up. Is it a stretch to add Donnie Darko to this category?

Really brilliant piece, especially enjoyed the part about romantics being born into an unromantic age.