From Egypt to Warsaw: A Cinematic Haggadah

DeMille, the Dekalog and A Real Pain: Finding the Divine in Broken Connections

Passover is approaching this week, with an ancient promise of renewal and liberation. It's always been my favorite religious holiday — and it's clearly the most cinematic.

Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments (1956) rests easily in my Letterboxd "Four Favorites." And despite the fact that it's aired annually on ABC, homaged by everyone from Mel Brooks to Eddie Murphy to James Cameron - I think it's actually underrated.

But if you're looking for an example of a man who gives up worldly power (Egypt and Anne Baxter’s Nefertiri!) in search of a deeper moral truth and liberation for his people — then Charlton Heston's Moses is one of the best Hollywood has ever produced.

The power of the film is its simplicity amidst its grandeur. Heston's Moses is a square-jawed American. He is liberating the downtrodden from tyrants. The miracles he calls forth to humble Pharaoh are epic and beyond belief.

Aside from the Creation and the Flood, "The Exodus" is a story where God's presence is strongest. An active force in the universe that acts for justice.

But what about when God's presence feels faint?

When markets are collapsing and society is polarized?

How do we tell the story of the Exodus when the times lack Technicolor?

WHEN GOD ISN'T PARTING SEAS

Alongside my annual rewatch of The Ten Commandments (1956), I've found myself drawn to two films that seemingly have little in common with DeMille's epic – yet they illuminate Passover's meaning in our fractured age with surprising clarity: Krzysztof Kieślowski's Dekalog (1989) and Jesse Eisenberg's A Real Pain (2024).

While DeMille sets his film in the deserts of Egypt, Kieślowski and Eisenberg set their cameras in Poland – another land of Jewish exile and mysticism, where trauma preceded return. One film crafted by a Polish Catholic during Communism's final days, the other by an American Jew wrestling with Holocaust memory. Forty years separate them, yet they explore the same spiritual terrain.

These unlikely companions reveal what divine presence looks like when God isn't parting seas or inscribing stone tablets – when liberation must be found in the spaces between people, in fleeting moments of connection within our screen-mediated, alienated lives.

The Polish train stations that appear in both works become more than mere backdrops; they transform into theological spaces where divine absence takes architectural form. These are settings where human connections are missed, abandoned, or – occasionally, miraculously – forged against all odds.

For viewers moved by Eisenberg's recent Oscar-winning film but unfamiliar with Kieślowski's masterwork, there's a cross-generational dialogue happening that feels almost providential. These films speak to each other across decades, revealing how our smallest human connections participate in creation's daily renewal.

CONCRETE CINEMA, CONCRETE COMMANDMENTS

The Dekalog was created during Poland's transition from Communist rule (1988-89). Kieślowski's ten-hour television masterwork corresponds to the Ten Commandments, though never explicitly stating which episode matches which decree.

This ambiguity is deliberate—a cinematic acknowledgment that moral principles cannot be reduced to rule-following but must be discovered within the texture of daily existence.

For viewers moved by Eisenberg's exploration of Jewish identity and historical trauma in A Real Pain, Kieślowski's Dekalog offers an essential companion piece—a work that examines the spiritual architecture underlying human connection across seemingly mundane situations.

Set primarily in a single Warsaw housing complex—concrete apartments whose architectural uniformity suggests both Communist collectivism and spiritual barrenness—the films explore moral quandaries through everyday encounters. The housing complex itself becomes a cinematic Mount Sinai where commandments are not handed down but worked through in painful human interaction.

Within this brutalist architecture, Kieślowski creates a surprisingly intimate visual language. His camera frequently finds characters reflected in windows, televisions, and mirrors—visual fragmentations that suggest spiritual disintegration.

When moments of genuine connection occur, his framing shifts from division to unity, from obscured to direct vision—a visual grammar of divine presence emerging through aesthetic choices.

GREEN SCREENS AND FALSE IDOLS

Without revealing the specific narrative journeys that make Dekalog (1989) such a profound viewing experience, we can identify how Kieślowski's visual language creates a theological framework that resonates with Eisenberg's contemporary explorations.

In Dekalog I (1989), Kieślowski examines our relationship to technology and certainty through a father's faith in calculation. The eerie green glow of computer screens creates a visual metaphor for false illumination—technology as modern idol.

When certainty fails, Kieślowski's camera discovers warmer light sources—visual transitions from false to authentic illumination that suggest spiritual awakening without didacticism.

Dekalog II (1989) presents a doctor confronting impossible ethical choices through consequential acts of deception. Kieślowski establishes this theological dimension through composition—placing the doctor physically above others during consultation scenes, shooting from low angles to suggest illegitimate authority.

The doctor's apartment overlooks the hospital, his gaze from the window a visual echo of divine surveillance that creates tension between power and responsibility.

By Dekalog VI (1989), Kieślowski explores how mediated experience creates spiritual alienation through the story of Tomek, who observes a woman through his telescope. The director creates a visual system of frames within frames—windows, telescopes, binoculars—that fragment reality.

When unmediated encounter finally arrives, Kieślowski shoots their interaction in sustained takes with minimal cutting, creating visual immediacy that mirrors spiritual presence.

These episodes—along with the complete ten-part cycle—offer viewers who connected with A Real Pain a deeper exploration of the theological questions Eisenberg raises. Kieślowski's work provides not answers but a visual language for contemplating divine presence through its apparent absence—a language that resonates powerfully with Eisenberg's Holocaust pilgrimage forty years later.

ROOFTOPS AND REVERBERATIONS

Eisenberg's Oscar-winning A Real Pain (2024) continues this theological exploration through two Jewish-American cousins embarking on a Holocaust heritage tour through Poland. David (played by Eisenberg himself) embodies anxious pragmatism – a family man whose routine has calcified into emotional distance. Benji (Kieran Culkin, whose performance earned him the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor) represents charismatic chaos – brilliant but wounded, perceptive yet self-destructive. Their contrasting relationships to inherited trauma create the film's central theological tension.

Their journey – funded by their late grandmother who survived the Holocaust – takes them through Warsaw and Lublin before culminating at the Majdanek concentration camp. Polish cinematographer Michał Dymek's camera places us not as detached observers but as fellow travelers, eavesdropping on tour group dynamics that shift between banality and profound revelation.

Eisenberg's visual language is architectural. Throughout the film, physical structures – doorways, windows, monument barriers – frequently separate the cousins within the frame, visualizing their emotional distance from each other and from history itself.

The film's approach to Holocaust sites achieves a delicate balance – neither exploitative nor sentimental. This restraint is particularly evident in the Majdanek sequences, which Eisenberg insisted on filming at the actual location. As he explained in interviews, his goal was "to depict Majdanek as it is now as a tourist site" rather than recreating it as a historical set. In this way, eavesdropping transforms into witnessing.

For Benji and David, there is no dramatic reconciliation, only small moments of connection that briefly overcome their alienation. The most powerful occurs not in any memorial space but on a Warsaw hotel rooftop, where the cousins smoke weed under the night sky.

Elevated above the weight of history below, they find a temporary space for authentic revelation. As they pass a joint back and forth, their conversation moves through reminiscence and regret until reaching a raw emotional truth – David finally admitting that after Benji's suicide attempt, he simply couldn't bear the thought of losing this brilliant, difficult pseudo-brother.

It's a recognition that sometimes absence stems from an excess of care we cannot express.

PSALMS FOR THE FRACTURED

These films resonate deeply with my own experience of the divine.

I’ve always had an ambivalence to the “rules to run the minutiae of your life”, pedantic form of Judaic observance.

I've settled on daily prayer as a means of deliberate mindfulness. I find it deeply comforting to take time each day to consider, praise and petition the god of Jacob. A god who's been with me since childhood - not some abstract concept, but a presence I've felt in moments of both joy and despair. I can't define this presence with theological precision, but I know it when I encounter it.

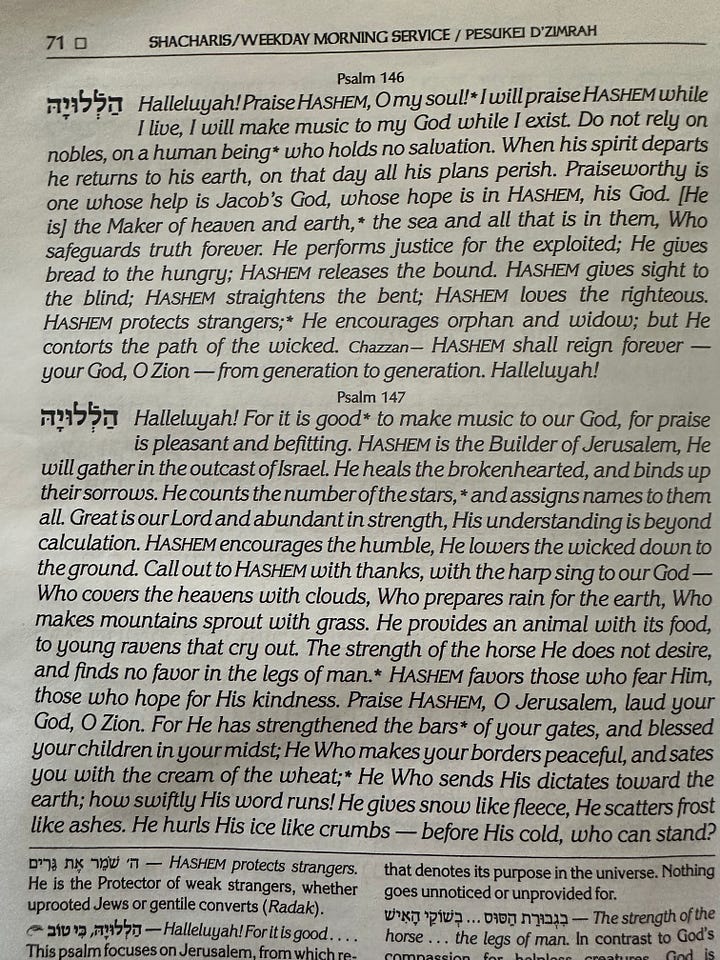

And while my personal experience may be ambiguous, the daily prayers of Psalms 146 and 147 are bracingly clear. They speak of a God who "executes justice for the oppressed" and "heals the brokenhearted" - not through miraculous intervention but through the actions of those who carry these words in their hearts.

They exhort us to:

"Put not your trust in princes, in mortals, in whom there is no salvation. When their breath departs, they return to the earth; on that very day their plans perish." - Psalm 146:3-4

These ancient words resonate across all three films, and are at the core of their portrayal of alienation and bondage.

Characters repeatedly place faith in human systems—science, law, property, surveillance—only to confront their fundamental insufficiency.

The warning of Psalm 146 becomes a central cinematic theme across both works, visualized through institutional failures and collapsing certainties.

DeMille shows us the glory of Egypt — its buildings, its treasure, its seductive luxury, but also the corruption and cruelty that lead Moses back to his people. The Pharaoh's gleaming architectural monuments and golden idols ultimately cannot protect him from divine judgment. His trust in princely power proves devastatingly ephemeral when confronted with authentic liberation.

The film's most shattering moment comes after the defeat of Pharoah’s army, and the death of Egypt's firstborn, and Yul Brynner's Rameses whispers in defeat, "His God... is God." It's a concession that echoes Psalm 146's warning about the impermanence of human power with devastating cinematic force.

Kieślowski creates images of institutional insufficiency—hospitals where healing is bureaucratic, courts where justice is procedural, schools where knowledge is rote. His camera finds the cracks in these systems—the moments where human need exceeds institutional capacity.

When legal proceedings fail to contain emotional realities, when technological certainty crumbles against human complexity, Kieślowski's visual language creates space for contemplating divine absence.

"The LORD builds up Jerusalem; he gathers the outcasts of Israel. He heals the brokenhearted, and binds up their wounds." - Psalm 147:2-3

When genuine connection does occur—those rare moments of grace in both works—they mirror the Psalm's promise of healing and gathering. Characters experience momentary alignment with divine presence not through religious ritual but through authentic human encounter.

These moments aren't sentimental but hard-won—emerging from conflict, misunderstanding, and failure rather than easy resolution.

Similarly, Eisenberg's visualization of healing occurs not in the expected spaces of memorial or monument but in profane locations—a hotel rooftop, a nightclub, a train station bench. His camera discovers moments of grace in these ordinary spaces, suggesting that divine presence emerges not in designated sacred zones but through authentic human encounter in seemingly mundane settings.

THE MECHANICS OF DIVINE PRESENCE

What elevates these works beyond moral tales into profound theological statements is their recognition that divine presence manifests through cinematic form itself. The medium becomes the message—each formal choice creating a visual grammar of divine revelation or hiddenness.

DeMille's approach is the most direct—divine presence appears through spectacular intervention. The burning bush speaks, the sea parts, the finger of God writes upon tablets of stone. Yet even in these moments of ostensible directness, DeMille's camera maintains a reverent distance. We never see God directly; we witness only the effects of divine action. The burning bush appears, but the voice emanates from off-screen (and it is Heston’s own) — present yet unseeable, a careful formal balance between revelation and mystery.

Kieślowski's silent witness figure—a man who appears briefly in each episode, observing critical moments without intervention—embodies a different paradox of divine presence. Initially appearing in the first episode as a man warming himself by a fire as events unfold nearby, he returns throughout the series, always watching, never speaking. His consistent presence across different stories suggests omniscience without omnipotence—divine attention without intervention.

Eisenberg, meanwhile, finds divine presence in the spaces between people—in the frame when two estranged cousins finally connect, in the momentary touch of hands, in the shared silence at Majdanek. His camera captures the moments when human connection briefly transcends historical trauma and personal alienation.

This visual approach creates a cinema that doesn't merely represent theological concepts but generates them through form. Each director's gaze becomes analogous to a different mode of divine attention—DeMille's as spectacular intervention, Kieślowski's as present but non-intervening witness, Eisenberg's as the connective tissue between isolated individuals

AN OBLIGATION OF RENEWAL

Since 2013, we've kept a tradition of inscribing the names of everyone who joins us in the back of our Haggadah. As our family gathers around the seder table this year, these names have become a living record of presence and absence – each entry a testament to connection across time.

My father, who truly loved The Ten Commandments always led our seders. His presence, missed the past four years, appears prominently across the rest of the entries.

Running my fingers over his name, I feel his absence and the ongoing power of his presence. Memory itself becomes a form of renewal, a way of transcending time's linear experience.

The ritual itself – the telling of an ancient story of liberation – becomes not just commemoration but participation in ongoing creation. We don't simply remember Exodus; we reenact it, renew it, make it present again.

This is the lesson these films teach, and what Passover itself embodies: that divine presence manifests not just through spectacular intervention but through our continued gathering, our persistent telling, our refusal to surrender to whatever man made affliction binds us.

As we reflect on Exodus this Passover – its liberation and its commandments – these films have helped deepen my connection to its ancient story.

DeMille gives us the spectacle, the grandeur of divine liberation in Technicolor certainty. Kieślowski offers us the commandments not as tablets from on high but as principles worked out in everyday human struggle. Eisenberg shows us what inherited memory looks like when we've forgotten why it matters.

These films, in their different ways, remind us that Exodus isn't an ancient event but today's challenge. Liberation demands both the spectacular and the intimate – Moses' outstretched arms at the sea and two cousins sharing a joint on a Warsaw rooftop.

Divine presence arrives not only thunder and flame, but in the moments we truly see each other.

WHERE TO WATCH

The Ten Commandments (1956)

PHYSICAL MEDIA: Available on 4K UHD, Blu-ray, and DVD from Paramount Pictures

BROADCAST: Traditionally airs annually on ABC during the Passover/Easter season

Dekalog (1989)

PHYSICAL MEDIA: Complete Criterion Collection Blu-ray/DVD set (includes both feature film versions of episodes 5 and 6)

SPECIALTY STREAMING: Available on Eastern European Movies with English subtitles

INTERNATIONAL OPTION: Available on MUBI in select countries

A Real Pain (2024)