Cognitive Frames: In the Room

Critical reviews of live performances from new cultural gatekeepers

“A taste for music, a taste for anything, is an ability to consume it with pleasure. Taste in music is preferential consumption, a greater liking for certain kinds of it than others…

And the pleasures of taste, at best are transitory, since nobody, professional or layman, can be sure that what he finds beautiful this year may not be just another piece of music to him next.

The best any of us can do about any piece, short of memorizing its actual sounds and storing it away intact against lean musical moments, is to consult his appetite about its immediate consumption, his appetite and his digestive experience.

And after consumption to argue about the thing interminably with all his friends.

De gustibus disputandum est,”

- Virgil Thomson, “Taste in Music”, The New York Herald Tribune (1940)

As music and culture critic for New York Herald Tribune during the WWII era, Virgil Thomson brought his skills as a composer to his influential columns and performance reviews. Intellectually fierce and clear in his preferences, Thomson championed a plain spoken approach to music criticism.

In the same article, Thomson explained his critical philosophy:

“The leaders of taste can no more create deliberately a mode in music than advertising campaigns can make popular a product that the public doesn’t want. They can only manipulate a trend. And trends follow folk patterns.

That is why unsuccessful or unfashionable music, music that seems to ignore what the rest of the world is listening to, is sometimes the best music, the freest, the most original — though there is no rule about that either”

This “middlebrow” approach understood that American tastes were open to a broad cross-section of musical influences — one that was free from old conventions and open to new ideas. One that placed the Viennese school of Mozart, Beethoven and Bach on the same level as the “Hot Jazz” that was evolving daily in the clubs a few Avenues over from his offices.

Open to cross-influence, and concerned with complexity, virtuoso performance and popular impact — this American approach to music criticism championed an era of “middlebrow” excellence.

When The New York Times reassigned four of its senior culture critics this summer - it was the final indication that the era of “middlebrow” criticism that championed excellence across American music culture was completely dead.

Charlotte Klein’s official obituary of rich cultural criticism for New York Magazine was filled with the sort of concern one might express to one’s mother when she calls asking why “MSNBC” is changing its name to “MSNOW”. Klein noted how the Chicago Tribune's film critic position disappeared for the first time since the 1950s, how the Washington Post and Vanity Fair shed longtime critics, how even the Associated Press ended its weekly book reviews after decades.

Klein introduced us to what Hearing Things founder Ryan Dombal calls "cool hunting" criticism—content focused on "sifting through the deluge of music that's put out every single day."

This curatorial approach represents something fundamentally different from Thomson's vision. Thomson digested and argued while today's criticism merely sorts and recommends. Where he saw criticism as democratic dialogue, algorithms see it as content curation.

But every ending creates an opening.

Cognitive Frames: In the Room

In the Room is our new journal of live music and event criticism.

By extending the democratic approach we’ve brought cinema to live performance we believe we can revive the lively middlebrow discussions of the Thomson era.

Thomson knew that "trends follow folk patterns." Real cultural movements don't start in critics' rows; they emerge from the full house, from every price point, from the democratic mix of perspectives that creates genuine dialogue.

We want to be in the room, so we can be in the discussion.

What We’re Covering this Fall

Our inaugural reviews will cover Gustavo Dudamel's opening week as the NY Philharmonic's Music Director Designate (September 11-16), featuring 22-year-old sensation Yunchan Lim performing Bartók's Piano Concerto No. 3.

Dudamel's appointment represents a generational shift at the Philharmonic, while Lim—who stunned the classical world winning the Van Cliburn Competition at 18—brings fresh perspective to Bartók's final masterpiece, composed during the Hungarian composer's exile in New York.

We'll follow this with the Metropolitan Opera's world premiere production of The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, which opens September 21 and runs through October 11. Mason Bates and Gene Scheer's adaptation of Michael Chabon's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel perfectly embodies our belief in artistic porousness: a story about Jewish comic book creators fighting fascism through Superman-like fantasies, now becoming opera at America's most prestigious house.

One of our favorite books of the aughts—we're excited to see how the Met transforms Michael Chabon’s epic about art, exile, and the birth of superheroes into opera.

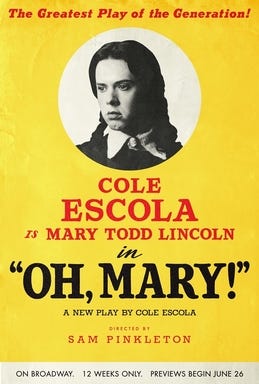

November brings Cole Escola's "Oh, Mary!" (November 8)—the Tony Award-winning comedy that reimagines Mary Todd Lincoln as a cabaret-obsessed alcoholic in the weeks before her husband's assassination.

Our trips to the Met continue with Mozart's Don Giovanni (November 15) and Strauss's Arabella (November 22).

We'll also be covering the 63rd New York Film Festival (September 26-October 13), bringing this same democratic approach to America’s most prestigious film showcase—from whatever screenings we can get into on our 6 film pass.

Join Us In The Room

“De Gustibus Disputandum Est” - Virgil Thomson reversed the old Latin maxim—he believed we SHOULD discuss taste. As the patron saint of “In The Room” we will follow his example.

Discussion itself is the point. Not to win, but to participate in the democratic conversation that keeps culture alive.

The veteran who's followed a band since dive bars brings different knowledge than the teenager discovering them at Governors Ball. The rush ticket holder at the Philharmonic, the all-day museum wanderer, the festival-goer choosing between three stages—each perspective illuminates something others miss.

We want to know why you bought that ticket, how you experienced the performance and the impression that it left.

In these polarized and often tragic times, we believe now is the time to recommit our public passions to art and music and human excellence.

We’re sharing what moves us. Share what moves you.

When professional criticism collapsed, we lost those conversations. What replaced them—algorithmic playlists, star ratings, recommendation engines—mistakes consumption for culture.

They can tell you what to listen to next but not why it matters. Only human experience can do that.

Thomson's era had their discussions in newspaper columns and concert hall lobbies, in late-night diners after performances.

Substack allows us to create new spaces for those same vital and human conversations. Every perspective from every venue helps us understand what culture actually means to the people experiencing it.

Join us in the room. Share what moves you.

Look for our first review this week and send your submissions to submissions@cognitivefilms.org.