Jacob Weintraub and I both survived the same boutique communications firm—one of those crypto-adjacent shops where “strategic” meant whatever the startup client needed it to mean that week. We were both good at the job. Neither of us misses it.

What I remember most about Jake wasn’t his facility with startup jargon (though he mastered it), but his ability to spot the actual human story buried underneath all that disruption theater. While others polished pitch decks for the next big thing, Jake saw the comedy, the tension, the unspoken truth that made it all absurd.

Now a full-time law student, we reconnected through Substack, where Jake now writes In Re: Everything about law, technology, and culture. When I told him Cognitive Frames was expanding beyond film criticism to cover live performance, he immediately got it: criticism that treats the audience experience as inseparable from the art itself.

His piece on Art is exactly what we’re after. Three men arguing about a white canvas becomes a mirror reflecting your own friendships, your own need for validation, your own carefully constructed self-image. That’s what In the Room is about—the moment live performance stops being something you observe and becomes something you inhabit.

Welcome, Jake. We’re glad you’re here! - D.H.

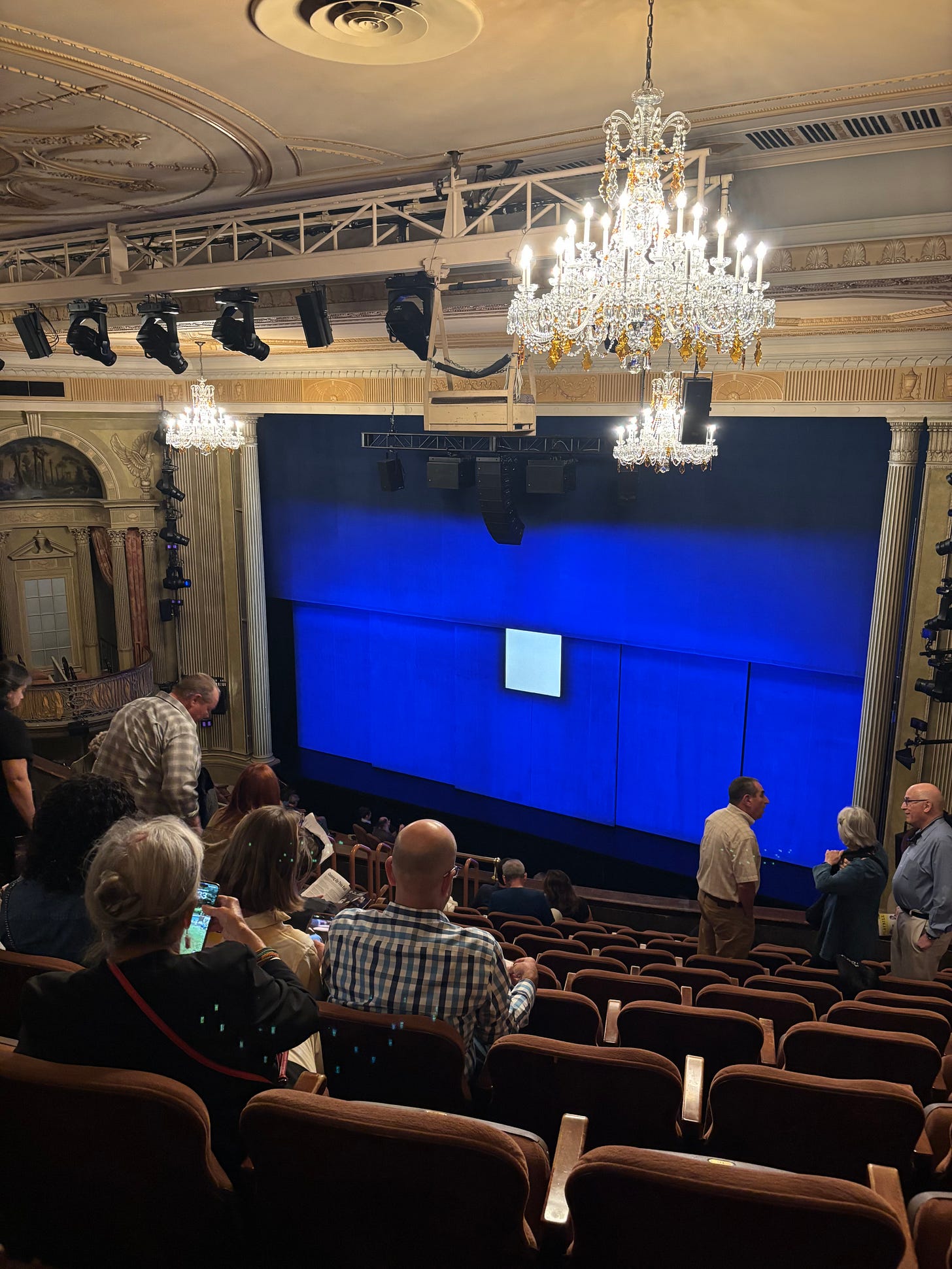

My girlfriend and I recently saw Art. We went to a matinee and were met with sweltering September heat, baking on the sidewalk while we waited to get in. Waiting there felt like a kind of tribute, an offering to the Broadway gods before the show.

Once inside, the staff moved us along briskly, almost dismissively. No smiles, no welcome. Not that I expected Disney World, but you don’t usually get that kind of terse reception on Broadway. It was funny in a way, like they themselves didn’t quite buy the hype. Maybe it was intentional - a little forewarning that mirrored the show’s own skepticism. Maybe the ushers were preluding Art with their own critique. Either way, that faint air of doubt felt almost tangible as we found our seats.

When the lights dimmed, the room snapped to attention. No grand overture, no dizzying set pieces. Just three men, a simple room, a few chairs, and a white “painting.”

I’ve seen the Broadway shows built to impress - the rising sets of Wicked, the hypnotic staging of The Lion King. Art isn’t that, nor does it try to be. It’s almost aggressively plain. The stage feels like a rehearsal room someone forgot to decorate. But that simplicity is a trap: it forces you to look harder, not at props or design, but at people, onstage and around you.

That’s what excited me. Knowing the show would live or die on dialogue had me eager. So often we lean on aesthetics to add value, or to distract from thin substance. Art makes no such attempt. The show hinges entirely on the words. In an era of short attention spans and endless video scrolls, I loved locking into ninety straight minutes of conversation. It even made me think of 12 Angry Men, a single room as a direct line into the machinery of relationships and human nature.

Art isn’t about art at all. It doesn’t want to be. It’s about friendship, and the quiet, ego-driven math that can live underneath it.

As the three friends argue about whether a blank white painting is “real art,” you start to feel the argument shifting. It’s not about taste anymore, it’s about validation. About what it means when the people who know you best suddenly stop seeing you the way you want to be seen.

Somewhere around the midpoint, I realized I wasn’t watching them anymore. I was thinking about my own friendships and how many of them were built on shared jokes or mutual ambition, and how fragile that foundation can be when the balance shifts. When one person grows faster, or slower, or in a different direction altogether.

That’s the genius of Art: it sneaks up on you. You walk in expecting three men arguing about modernism, and by the second act you’re thinking about your own worst moments - times you mistook someone else’s success for a threat, tried too hard to be understood, or failed to see a friend’s frustration wasn’t really about you at all.

The play reminded me that our own self-image is often just as blank as that white canvas - something others project meaning onto. We tell ourselves we’re the “main character,” the reasonable one, the glue holding things together. But to everyone else, we’re just another part of the composition. Sometimes background, sometimes accent, occasionally the thing that throws the whole piece off balance.

The older I get, the more I think friendship isn’t about finding people who see you exactly as you want to be seen. It’s about being okay when they don’t and realizing you can still love someone even when their version of you doesn’t line up with your own.

That’s what Art leaves you with, not the laughter or the lines, but a kind of uneasy quiet. The recognition that life is lighter when you stop needing to be the protagonist all the time. When you can sit in the back row, sweating and squinting, and still feel lucky just to be in the room.

Life gets a lot more fun when you can celebrate other people’s moments instead of resenting the ones you missed. I hope I can keep learning, and trying, to find beauty in a blank canvas. And if I can’t, I hope the people I love will help me on the way.

Jake Weintraub is a first-year law student and the writer behind In Re: Everything, a Substack exploring where law collides with technology and culture. After several years in strategic communications advising emerging tech companies and publicly traded firms on media and regulatory narratives, he stepped away to reset his perspective before starting law school - tutoring students across New York City and working in retail. He credits that chapter with refining his patience, perspective, and ability to tailor communication to any audience.