A New Romantic Cinema Defined 2025

The year's top 10 reveal the strength of an emerging counterculture

For fifteen years, the entertainment industry convinced itself that the audience couldn’t be trusted. That we needed to be managed. That the safest path was giving people exactly what the data said they wanted—familiar IP, familiar beats, familiar resolutions.

Nothing too challenging. Nothing that might lose the second-screen scrollers. Content engineered to go down easy and ask nothing in return.

The machine printed money. Marvel became the most successful franchise in film history. Netflix signed up hundreds of millions of subscribers. The content pipeline flowed.

Finish something and immediately forget it. Scroll for the next thing. Look for the next hit of frictionless entertainment that passes the time without requiring anything from you. Don’t criticize! If people like it, it must be good.

The best films of 2025 demonstrate a renewed and Romantic response to this optimized, populist decadence.

They’re not safe. They assume an audience capable of handling ambiguity and moral complexity and stories that don’t wrap up clean.

They’re betting that the audience Hollywood spent fifteen years underestimating is smarter than the data suggested. And a New Romantic audience is responding.

Sinners crossed $365 million. Weapons turned $38 million into $269 million. Marty Supreme just posted the best per-theater average in A24’s history and a $27 million Christmas opening (and counting). People are talking about movies again.

The pull toward real things is everywhere right now, because the counterculture of the 2020s is more aesthetic than movement. Its primary ethos is to choose human presence and connection over techno-optimized convenience.

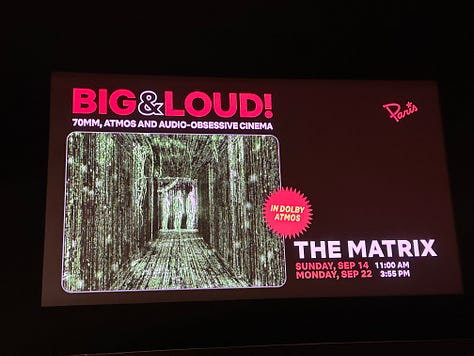

Vinyl over Spotify. The repertory screening in 35mm over the couch. Undiscovered gems on 4K Blu-ray over streaming shows intended to go nowhere. Concerts with live instruments over backing tracks. Classic institutions like the NY Philharmonic being reinvigorated with New Romantic energy.

Live events, readings, screenings are emerging everywhere. Kavalier and Clay is being brought back for a second run at the Met Opera. Even Netflix has become one of the top repertory programmers in New York City at the Paris Theater in midtown.

The New Romantic counterculture is suspicious of systemic, all-encompassing ideologies. It’s exhausted by ease that offers no satisfaction. It suspects that what we lost in the pursuit of convenience was the very thing that made culture worth having.

I’ve become somewhat enamored with the Metropolitan Opera this year. Every time, I’m struck by the same thing: this is what it feels like when everyone in the room agrees to pay attention to the same thing at the same time. No phones. No second screens. Just presence. Just the work and the audience in dialogue. The soprano holds a note and two thousand people hold their breath together.

You must be in the room to experience the sublime.

That’s what the best of 2025’s cinema offered. One person’s vision, uncompromised, asking an audience to be present. Given their success - one has to be optimistic about where this counterculture is headed.

Honorable Mentions

Not every great film fits neatly into a thesis. Some are simply well-made—craftsman’s work that reminds you why you fell in love with movies in the first place. Others push against the New Romantic current while still demanding presence. These are the films that didn’t quite crack the top ten but deserve recognition for what they offered audiences willing to show up.

Love Letters to New York

These filmmakers understand that cities and its outlying areas are characters. That streets have memory. That the best New York-centric films aren't just set here—they're about here.

Materialists — One of the best-looking New York films of the past decade. Celine Song shoots Manhattan like she’s afraid it might disappear—the specific restaurants, the particular light in a particular apartment, the way wealth moves through certain neighborhoods.

This improved considerably on second viewing, and I suspect will only grow in estimation with age. The film feels like a throwback to the great ‘80s New York dramas like Working Girl or The Secret of My Success—films that understood ambition as a New York story.

Highest 2 Lowest — A worthy variation on the Kurosawa masterpiece, transplanted from Tokyo to the boroughs. Spike loves New York and the Knicks and Kurosawa as much as I do, and like 25th Hour and Summer of Sam and Do the Right Thing, this is a love letter to the greatest city in the world. The class dynamics hit differently when you know these neighborhoods, when you’ve ridden these trains, when the geography of inequality is your daily commute.

After the Hunt — This is set at Yale, not Columbia, and despite Luca’s best attempts at cosplay, Woody would’ve paced it better. But Guadagnino captures something essential about academia—the dinner parties, the affairs, the way ideology curdles into performance among the professional class. I suspect ATH will only rise in estimation when people ask “How the hell did we end up here?”

Genre: Subtlety and Spectacle

The New Romantic sensibility doesn't reject spectacle—it demands that spectacle mean something. These films range from intimate spy games to cosmic demon-hunting, but each trusts the audience to follow without hand-holding.

Black Bag — Much better spycraft than 85% of the Mission: Impossible series. Soderbergh strips the spy thriller to its essentials: two people in a room, each trying to figure out if the other is lying. Human, sexy, and lots of great nonsensical intrigue. Michael Fassbender and Cate Blanchett don’t jump out of planes or onto trains—because they don’t have to.

Bugonia — I’ve often said that if David Muir unzipped his face one night “V” style and said “the invasion began 25 years ago, surrender humans,” it would just be another day that ends in Y. Lanthimos’s brilliantly intense and shockingly funny film does nothing to move me off my priors. His particular brand of absurdist horror—where the comedy and the dread are indistinguishable—continues to evolve in fascinating directions.

Zootopia 2 — The best Disney animated film in a decade? Surprisingly heartfelt, timely, and exciting. I came in with a cynical, anti-IP, corporate money-grab point of view and this film won me over completely. It earns its sequel status by going darker and more politically complex than the original dared. I could watch a Zootopia mystery once a year if they keep up this quality.

Ne Zha 2 — The best kung fu, demon-hunting, dragon-riding epic you’re going to see this year. Maybe any year. Chinese animation has been building toward this moment, and the result is staggering—visual imagination that puts most Hollywood blockbusters to shame.

Avatar: Fire and Ash — A harsher, meaner, and ultimately less satisfying trip to Pandora. This is the series’ Return of the Jedi—where a lot of the trilogy’s best ideas and critical plot points remain unresolved. Still—no one does spectacle like James Cameron, and this film is a complete trip to see in theaters. I will always welcome another visit to Pandora.

The Top 10 of 2025

These are the films that embody the New Romantic vision most fully—auteurist works that trust audiences and find meaning in human connection rather than systematic thinking.

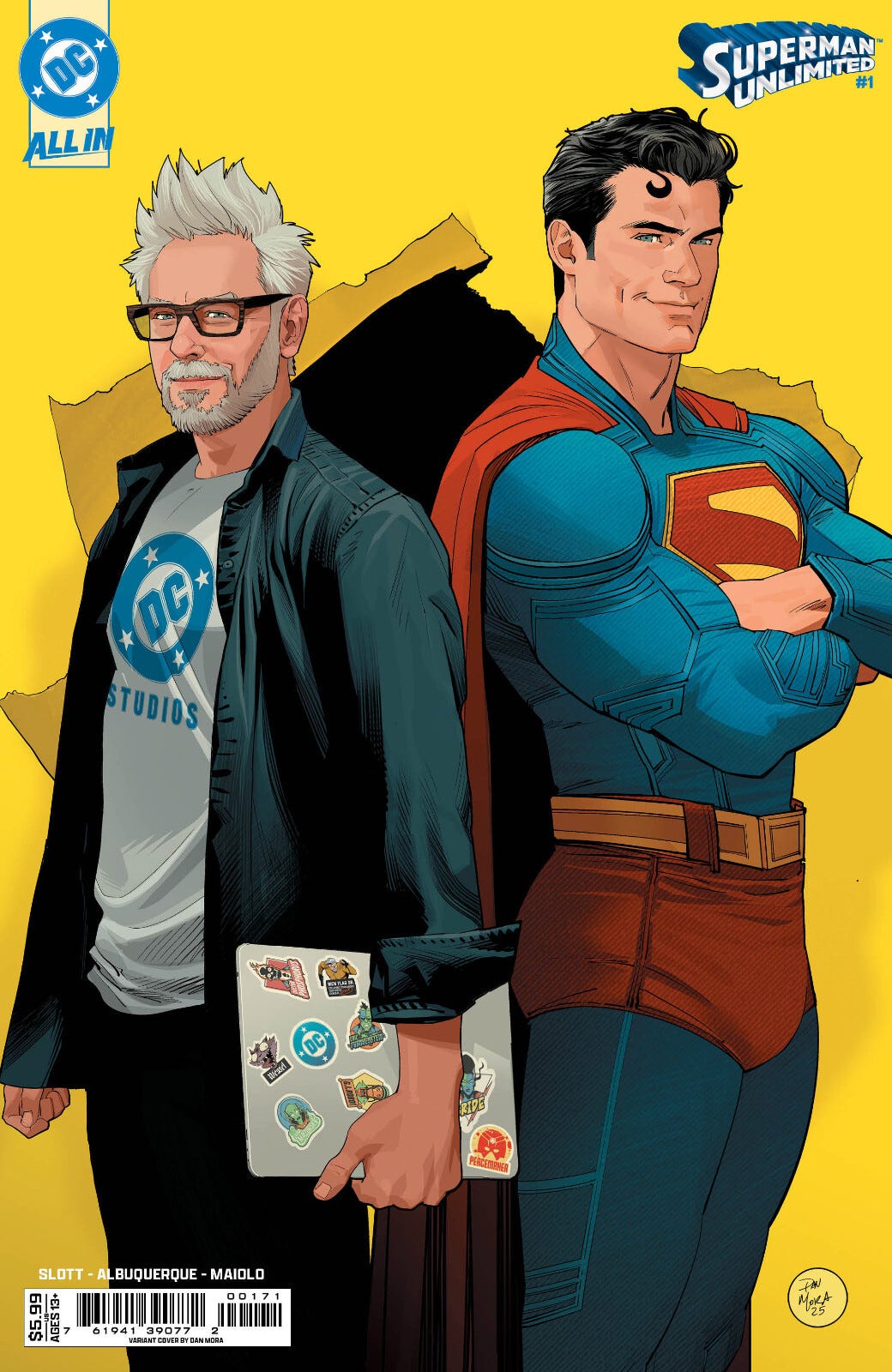

10. Superman

Superman means a lot to me.

Despite its imperfections, Superman understands why Superman means a lot to everyone.

It’s fitting that Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s Superman breaks his chains as the opening to DCU films. From the first time Siegel and Shuster put pen to paper, Superman has stood beyond political ideology. Kindness. Truth. Justice. Goodness. Not deconstructed goodness. Not “complicated” goodness that’s actually moral compromise. Just goodness—four-color, sincere, unabashed, unapologetic.

Gunn’s brilliance is understanding that in 2025, just as in 1938, these are radical stances. Despite his alien origins, Gunn restores Superman’s status as the most humanist superhero. He knows the names of the civilians Luthor mindlessly kills. He rejects his “true” Kryptonian mission in favor of humanity. He saves the squirrel.

Compare this to Marvel’s decade-long approach where every hero must be “complicated”—morally compromised, emotionally hedged, sincerity undercut with jokes to protect audiences from feeling too much. Compared to the MCU’s soulless Fantastic Four (2025) which shows us a family without emotional depth, Superman refuses that protection.

In an age trained to distrust genuine feeling, Gunn offers radical earnestness as revolutionary act. Kindness as punk rock.

Look up in the sky.

9. Weapons

What if the reason everyone is acting so strangely is the reason we all suspected?

What if the demon we’re confronting is just the very human inability to let go—the inability to cede the world in its natural cycle of renewal?

If the Frankenstein myth is about creating life that destroys us. Weapons shows how preventing death becomes monstrous.

The film’s genius is making its central question visual: What if our desperate refusal to accept natural cycles—death, loss, the world moving on without us—became physical? What if the sacrifice of the best years of our lives and of our children were made tangible? What if you could see and touch and pity our inability to let go?

Cregger constructs his horror through accumulation rather than shock. Every scene adds another layer of wrongness, that persistent dread of waking up on a bad day, in a bad month, in the current era—and slowly realizing something fundamental has broken. The film doesn’t offer many jump scares. It offers the more terrifying recognition: we’ve been trying to optimize our way out of mortality, and that refusal to accept limits has consequences.

The demon in Weapons isn’t evil—it’s sympathetic, even tragic. Human enough to inspire kindness, empathy, and pity. It’s what happens when love curdles into control, when care becomes refusal to release. The horror emerges from recognizing ourselves in the monster.

Where the humanist films on this list find grace in everyday relationships, Weapons finds terror in our refusal of those relationships—choosing control over acceptance, fighting death rather than ceding the world to renewal.

Weapons lets the dread seep into you. I left the theater unsettled in a way that took days to shake.

8. F1

We are so back!

Bruckheimer filmmaking at its absolute finest. Real movie stars, super fast cars, incredible production value. It’s got romance. It’s got stakes. It’s got training montages and fireworks and teamwork overcoming longshot odds.

After Top Gun: Maverick, Joseph Kosinski has become the premier director of pure kinetic cinema. He understands spectacle requires reality. When Tom Cruise actually flies a jet, you feel it. When Brad Pitt actually sits in a Formula 1 car going impossibly fast, inches from death, you feel that too.

No LED volumes. No CGI slop. Just real cars, real speed, real danger captured on camera. The pleasures are old-fashioned—craft, tension, physical reality. The kind of spectacle that demands you be present because you can feel the difference.

F1 is not a complicated film. It doesn’t need to be. There’s a washed-up driver getting a second chance. There’s a young hotshot who needs humbling. There’s a race to win.

I’m a cowboy, on a steel horse I ride. Yee-Haw!!!

7. The Phoenician Scheme

The Phoenician Scheme hit me hard.

Anderson smuggles his deepest anxieties—about meaning, mortality, and God’s silence—into a madcap caper that somehow holds it all together.

For those of us navigating middle age and its particular terrors, this feels like Anderson made a film directly for us. The film channels everything from Italian crime films to Bergman’s dreamscapes to Vlacil’s surreal Catholic guilt, yet it remains unmistakably Wes Anderson.

The father-daughter relationship is always fraught with questions of legacy, mortality, and responsibility. Underneath the whimsy and the assassination attempts and the immaculate production design, there’s a man reckoning with mortality. And a daughter deciding whether grace extends even to arms dealers.

When systems fail—when ideologies reveal themselves as empty, when even God stays silent—what remains? The irreducible human connections that can’t be explained. Beauty as the only honest response to divine silence.

It is Wes Anderson’s most triumphant film since The Grand Budapest Hotel.

6. Eddington

What cracked in 2020?

Was it the culmination of long-standing injustices finally rupturing the surface? Or did we all just go collectively insane from being trapped inside with our screens? The answer hardly matters when fear and frustration twist the mind the same way, giving license to our worst and most animalistic impulses.

Eddington takes us back to May 2020 and shows a very human path toward anger and violence—one that perhaps we’re still on. Like Nashville and No Country for Old Men, it presents American division and violence as both cyclical and inevitable.

Aster won’t let us escape the brutal truths of those times. While we performed our politics for each other, tearing our communities apart over masks and protests, the dehumanizing march of big tech carried onward.

Every character—progressive or conservative, conspiracy theorist or centrist—is performing. And their performances serve powers that profit from division. Every character has grievances that are justified. Every character uses bad information to make terrible choices.

As Aster insisted: “the movie is just really about a data center being built.” While the town tears itself apart, algorithmic capitalism quietly advances. By the film’s end, after the violence erupts, we see the conspiracy theorist mother-in-law at its ribbon-cutting ceremony, blessing the very development she once manically opposed.

Much like After the Hunt—many of the negative takes are about the film’s politics, or lack thereof. But that’s exactly the point. The systematic politics—Left or Right, progressive or reactionary—are performance.

Excuse-making, while forces that undermine us all advance and our IRL neighbors suffer.

5. Blue Moon/Nouvelle Vague

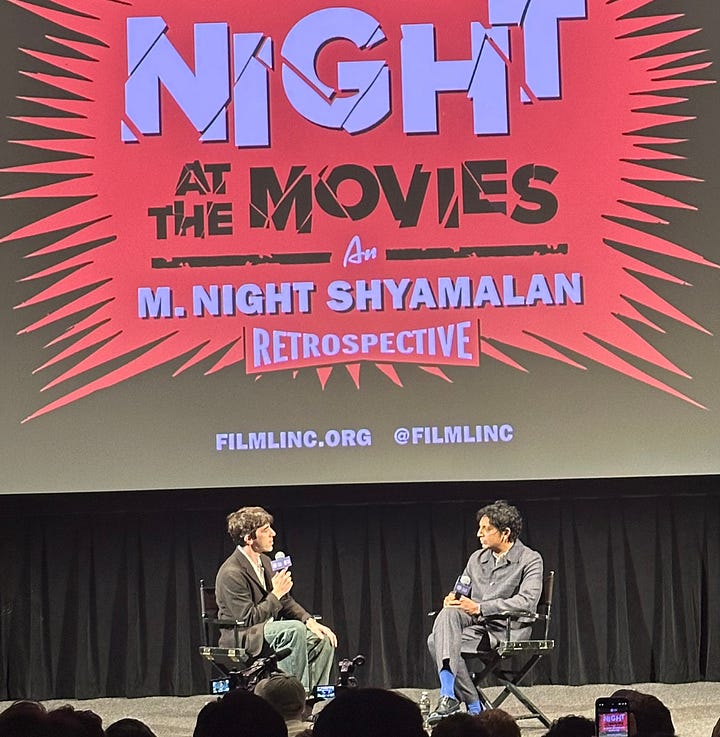

What a New York Film Festival for Richard Linklater.

Bias plainly stated — I saw these films as a double feature with my daughter—Blue Moon in the afternoon, a conversation with Ethan Hawke and Andrew Scott afterward, then straight into Nouvelle Vague with Linklater and cast. Two films about creative geniuses, so different in tone, that together reveal something essential about the New Romantic vision: creation is the most human act there is. Which means it carries all our human baggage with it.

Blue Moon shows us the shadow side—what happens when jealousy, irrelevance, and alienation poison the well. Lorenz Hart wrote perfect songs like “Bewitched.” and “Blue Moon.”, but human beings are not capable of such perfection. We’re tortured, petty little creatures—and when we give into the dark voices in our heads, well, it ends in dark places.

I knew little of Hart before this movie, save for his music. Such a beautiful soul—would that he could’ve seen that beauty in himself. Ethan Hawke and Andrew Scott give phenomenal performances, showing us a partnership where genius becomes entangled with need, where the intimacy that produces great art also produces devastating pain.

Nouvelle Vague is the antidote—creation at its most joyful and generative. No one makes a hangout movie like Linklater. Two hours with the crew of Cahiers du Cinéma in their prime, inventing modern cinema over coffee and cigarettes. Here the creative energy is pure—focused on the art itself, attracting and building and generating momentum because these young critics believe so completely in what they’re doing. The rivalries exist, but they haven’t yet curdled into destruction. The friendship is still feeding the work.

Together, these films argue that human connection is what makes creation possible—and what makes it dangerous. No AI program could have produced the Rodgers and Hart songbook or the French New Wave. These emerged from specific people in specific rooms, bringing their whole flawed selves to the work.

The Hawke-Linklater pairing embodies this creative intimacy. They made the Before trilogy together—three films across eighteen years, tracking a relationship in real time. They made Boyhood, filming the same actors over twelve years. They understand duration. They understand how people change. This is what auteurist cinema offers that franchise filmmaking cannot: a decades-long conversation between collaborators who trust each other, who’ve grown together.

Both films rest easy within Linklater’s distinguished filmography.

4. Sinners

There’s a scene late in Sinners where the devil sits down for a drink with our protagonists. Not to terrorize them. Just to reminisce. Kick around old times like an old friend. Hear those real Blues.

It’s one of the most unsettling moments I’ve experienced in a theater this year—not because it’s traditionally horrifying but because it’s intimate. The devil isn’t an algorithm. He’s someone you know. Someone who’ll buy the next round.

Honestly, I didn’t know Coogler had a movie like this in him. One of the more powerful films about the true nature of the devil I’ve seen.

Robert Eggers’s Nosferatu offers the classic Gothic vision of the devil as all-encompassing darkness, sickness, and contagion. Sinners knows better.

Sinners knows the true lies the devil shares. Knows that we have more in common with the devil than we like to admit. That sometimes, it’s good to have a drink with him and kick around old times.

The devil in Sinners is your brother whom you invited in. Who knows your weaknesses because you shared them. The film draws from From Dusk Till Dawn, from every folk tale about Charlie Patton and Robert Johnson at the crossroads—but it understands these aren’t about supernatural deals. They’re about the human capacity to choose what destroys us.

Evil isn’t systematic or abstract. It’s intimate, personal, human-scale. The devils that plague us aren’t some impersonal force like Thanos, but someone you know. Someone who’ll gladly buy the next round and truly, truly appreciates the good shit.

Reminiscent of Larraz—particularly Vampyres—but considerably less visceral. Sinners captures the same sultry appeal.

3. No Other Choice

Family first!

Park Chan-wook can always be counted on for an intense ride—but No Other Choice is one of his most relatable films. Particularly in my demographic.

War excuses so many inhumane acts, for the most noble reasons or intentions. The performances in this film quite literally bring the war home. A complete triumph in exploring the psychology when a family man quite literally has no other choice.

The film is centered on an incredible performance from Lee Byung-hun.

But here’s what haunts me: the title is the lie systematic thinking tells us. There’s always another choice. The system—war, duty, nation, ideology—convinces us otherwise. It narrows our vision until violence feels inevitable, until we believe the only way to protect the people we love is to become something monstrous.

2. One Battle After Another

What is wrong with America?

Are we racist, militarist right-wing psychopaths, ready to round up innocent families and factory workers? Are we Marxist terrorists, focused on impotent, performative acts of violence and hung up on pedantic language and outmoded ideologies?

Paul Thomas Anderson has been circling this question for three decades. Since Boogie Nights traced the rise and fall of the American dream through the San Fernando Valley porn industry. Since There Will Be Blood watched capitalism and religion devour each other in the California oil fields.

One Battle After Another is his most direct confrontation yet—a $140 million screwball revolutionary epic with the weight of American violence underneath.

Loosely adapted from Pynchon’s Vineland, the film follows Bob Ferguson (DiCaprio), a washed-up member of the radical group “French ‘75,” scrambling to save his daughter Willa when his revolutionary past comes crashing back. Sean Penn plays the fascist colonel pursuing them with the kind of unhinged menace that makes you laugh until you realize you’re not supposed to be laughing anymore.

Like many New Romantic films, OBAA understands that politics are pretext and violence belongs to everyone equally. The ideological labels are costumes and justifications for an exercise in power, or vengeance or assuaging fear.

The French ‘75 need their revolution—despite the human lives they ruin. The Christmas Adventurers advocate for racial purity until it becomes inconvenient for business. Everyone’s fighting for America while destroying the very people and values they claim to save.

The only real heroes of the film — Willa, Bob, Sensei — are those who choose family over ideology.

And maybe that’s the hope—Willa, who inherits this mess, seems to understand her mother’s failures. That the revolution isn’t in the grand gesture but in the daily act of staying. Of choosing family above all.

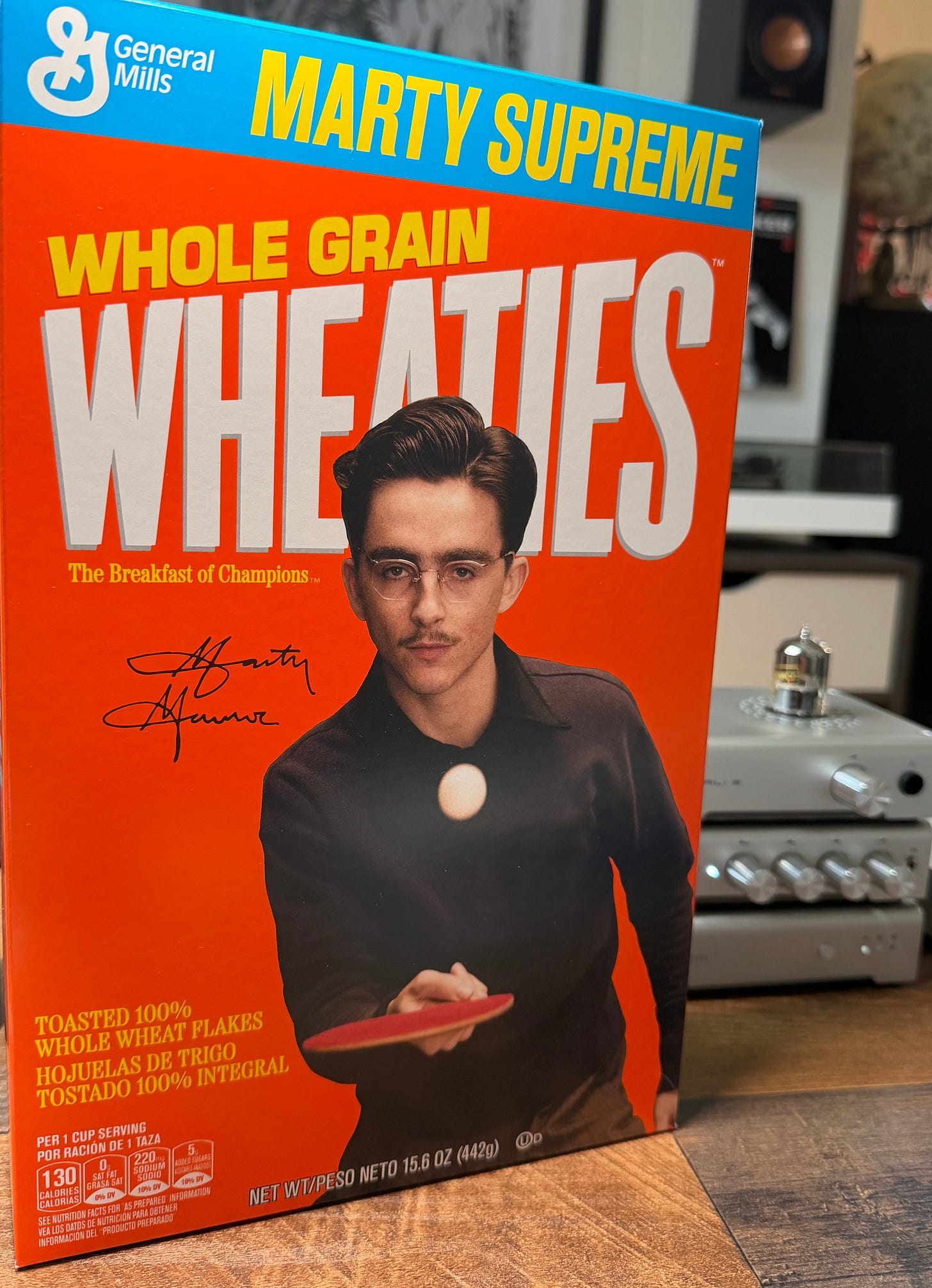

1. Marty Supreme

Marty Supreme is the ultimate paean to Jewish striving.

I’m still coming down from the madcap high of the year’s best movie. A Bernard Malamud novel’s worth of characters refracted through tropes of the heist, the sports film, and the period piece.

Marty Supreme puts the attraction and danger and seduction of the American dream at its center. Along with its benefits. And its soul-crushing defeats.

This is a film about what it costs to be great. What it costs to want to be great. The specifically Jewish hunger to prove yourself in a country that promises greatness to everyone - no matter what your background, if you can respect the hustle. No czars. No Nazis. Nothing standing in your way.

“Hitler’s greatest nightmare” as Marty states so plainly.

But in the pursuit of material happiness - you can win every match and still lose everything.

Josh Safdie understands something essential about the American hustle: it’s not a system you can game. Marty tries. God, does he try. He schemes and angles and finds every edge, every workaround, every way to beat the house - no matter the cost to himself, his friends or loved ones.

And the film lets you root for him—lets you believe, for a while, that hustle and talent and sheer will can conquer the machinery of the world. That in fact, post World War II, an entirely new and modern world had arrived. This time would be different!

But here’s what makes Marty Supreme the best film of 2025: it shows you that even when you achieve these goals, you can still lose big.

No one cares about your hustle. It will grind you down or spit you out. Trophies, whatever form they take, cannot keep you warm.

What saves Marty—what saves any of us—is the thing he almost throws away chasing greatness. Family. Love. The people who knew you before you were somebody and will be there after the world forgets your name.

Chalamet has been a movie star for years. Marty Supreme might make him an icon.

These ten films are proof that the New Romantic counterculture has arrived.

They all understand what Marty learns the hard way: the systems we try to game can never give us what we actually need. Only people can do that.

The pull toward real things is just beginning.

Happy New Year!

Weapons is pretty great.